The first smack to the face feels like an ambush. I windmill my arms, untangling myself from a dense spider web. I swat silk from my hair and neck. Hoping the sneaky web-spinner didn’t hop inside, I flip open the hood of my hiking shirt. Before I think to stop walking, I stumble through another web and repeat the entire process.

I’m hiking the Whites Creek Trail through dense woods of the Irish Wilderness in the southeastern Missouri Ozarks. So far, nothing is quite like I planned. For one thing, it’s 6 a.m. in early July and I’m already sweating through long pants and sleeves. Demonstrated by all the spider webs, plus poison ivy encroaching on the branch-strewn trail, most people don’t hike in the Ozarks during midsummer. Smart people.

I learned about the 16,227-acre Irish Wilderness years ago, when passing through on my first paddling trip down the Eleven Point National Scenic River. Ever since, I wanted to explore the interior on foot. Learning more about the outlaw history of the region only deepened my curiosity.

During the Civil War, a community of Irish immigrants vanished amid the violence of guerilla warfare fought throughout the border states. One such band of Confederates was the ruthless Quantrill’s Raiders, who traded vengeful atrocities with pro-Union guerillas. Among these murderous raiders were later bandits like the infamous Frank and Jesse James.

After the war, as entrenched political violence lingered throughout Missouri, a series of daring robberies began, with the targets typically being Unionist-controlled enterprises. The first was a bank in Liberty, Missouri, in February 1866. Next came a bank in Richmond, Missouri, where three citizens were killed during a shootout. Another bank was robbed in Russellville, Kentucky, in 1868. It’s not clear that the James brothers committed each crime they were credited with, but they were certainly involved in some of them.

It was the bank robbery in Gallatin, Missouri, during December 1869 that made Jesse famous. Not for a big payday but because Jesse shot and killed the cashier, former Captain John Sheets, confusing him for a different Union captain who had killed the ruthless Confederate guerilla leader, Bloody Bill Anderson.

The James brothers were suspected, and when a posse arrived at their family farm, the two brothers burst from a barn on horseback, firing their guns while escaping. In a letter to newspapers, Jesse claimed innocence, saying they fled due to fear of being lynched by Unionists. His fear likely had merit, given Jesse’s stepfather had been hanged from a tree by Union militiamen who wanted information about Confederates. Jesse, himself, had been shot in the chest (and almost died) in an ambush by Federal forces just after his guerilla band surrendered. In a borderland state still seething with post-war rage and acts of vengeance, Jesse James soon became an anti-government hero for his crimes against the enemy.

Exploring the Irish Wilderness. (Mike Bezemek)

While the brazen robberies continued — the ticket office during the Kansas City Exposition, derailing the Rock Island train in Iowa while wearing KKK hoods — a former-Confederate newspaper writer with a flair for the dramatic christened them 19th century Robin Hoods.

Though records are spotty, the James Gang occasionally used routes and hideouts throughout the Ozarks for getaways after robberies. In mid-January 1874, they robbed a stagecoach near Hot Springs, Arkansas. Afterward, they headed north, through the mountainous region I’m visiting, on their way to their next robbery.

Only legends and rumors suggest that Quantrill’s Raiders and the James brothers passed through the actual borders of the Irish Wilderness. But given this is one of the few parts of the Ozarks preserved like it was during the 1800s, a hike here feels like a good start to tracking Jesse James’ activities in the Ozarks.

My original plan was to backpack the 18.6-mile loop during the spring, spending a few days exploring. When the pandemic delayed my field season for four months, I switched to an early morning hike to avoid peak heat. I mean, the outlaws were on the move year-round, so how hard could it be to complete a half-day hike?

As I push deeper into the wilderness, beams of sunlight shine through gaps in the leafy oaks. One warm patch illuminates a few ticks clinging to my pants. I give up on using my hands to clear the spider webs from the trail. I grab a branch and wave it rhythmically in front of me, like the baton of a drum major marching through the Ozarks, high kicks included. If some backwoods hunter takes a potshot in my direction, it’s not because I look like a deer. They just hate marching bands.

It’s slow going, occasionally having to bypass the overgrown trail and hike through nearby woods. After 3 miles, I descend steeply to Whites Creek. The rising heat suggests turning around, so I linger at a spring-fed pool to cool off. When the outlaws did pass through the Ozarks, springs like this would have been critical water sources for them and their horses.

On my return hike, I cross paths with a large trapdoor spider. It briefly sprints toward me, so I jump out of the way. Probably tracking its own quarry? Next, I pass a brown spider curled in a ball on a leaf. Clearly, outlaws weren’t the only ones who hide around here. I find the parking lot still empty, except for my truck, so I wash my clothes in a bucket and take a bandanna bath with poison ivy soap.

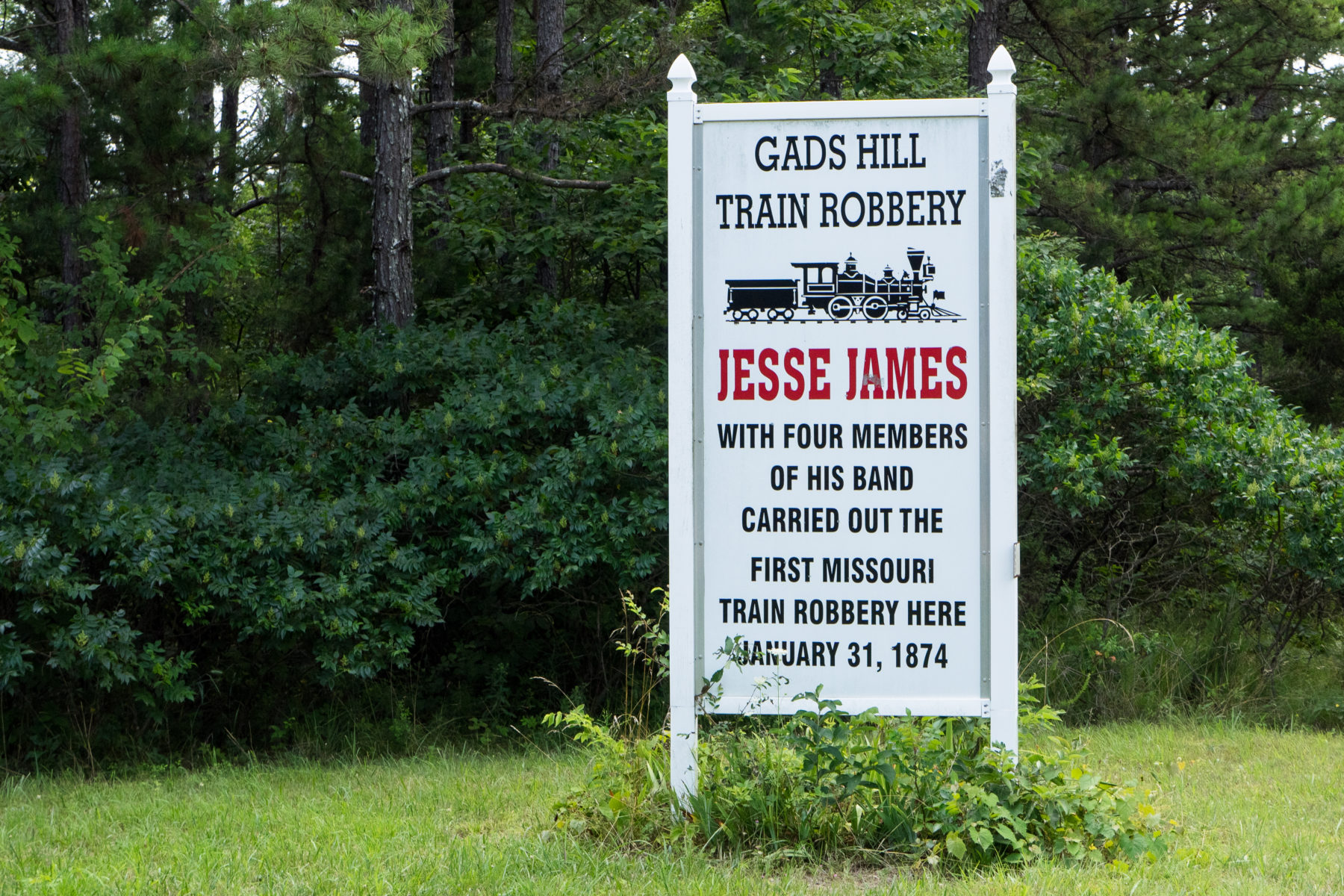

Driving north, the James trail becomes more certain — and air conditioned. Seventy miles on winding and diving Ozark highways leads toward the robbery site. Along the way, a summer of hyper-partisanship is on display. Rusty pickup trucks sporting massive confederate flags seem to be on patrol. When I roll into the tiny town of Gads Hill, I blink and roll out the other side. Circling back, I stop near a large sign which marks the event.

Marker at Gad’s Hill, Mo. (Mike Bezemek)

On January 31, 1874, the four-car Little Rock Express, on its way from St. Louis to Texarkana, was approaching Gads Hill when a man stepped onto the tracks waving a red caution flag. The switch had been thrown, and the train screeched to a halt on a siding. Five men, wearing masks and cavalry clothing, armed with revolvers and shotguns, surrounded the train.

Three men climbed aboard, first rifling the mail car, then emptying the express car safe, and finally robbing the passengers and crew. As the bandits worked, they mixed threats with jokes. Some jabbed the passenger’s ribs with pistols. One quoted lines from Shakespeare. A robber swapped hats with a passenger. Another wrote in the express agents’ receipt book: “Robbed at Gads Hill.”

Before departing, a bandit — some say Jesse James — left a telegram to be sent to the newspaper. Apparently, the gang took issue with recent descriptions of them by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

“The most daring train robbery on record,” began the telegram before listing the events and amount stolen, later redacted by authorities but possibly around $10,000 — a cool quarter mil in today’s money.

“The robbers are all large men, none of them under six feet tall…all mounted on fine blooded horses,” continued the telegram, ending with a plug of the region: “There is a hell of excitement in this part of the country.”

With the first peacetime train robbery in Missouri complete, the five men rode off into the Ozarks.

Abandoned cabin in the Ozarks. (Mike Bezemek)

Before following their tracks, I wander around Gads Hill. It’s pretty clear why the gang chose this town for the robbery. Like the 1870s, there are only a few buildings. Today, the main difference is a massive aggregate mine sits next to the railroad tracks.

After the robbery, the gang’s precise escape route is uncertain. There was a full moon on that Saturday in 1874, so it’s possible they rode through the night. Some writers have them heading south first, while most eventually place them 60 miles west of Gad’s Hill before stopping somewhere in Shannon County. To reach this alleged hideout, after crossing the Black River, they would have navigated through the rugged country surrounding the upper Current River.

On my drive west, I pass many abandoned Ozark cabins. Most seem to be from the 20th century, but some might have been around during the outlaw era. I decide to camp in Montauk State Park, at the headwaters of the Current River, and start exploring from there.

Dropping by the gift shop, I speak with an old timer who sits behind a plastic barrier. He repeats a variation of a story that’s told around these parts about the Howell-Maggard cabin, a restored log structure in Ozark National Scenic Riverways.

Supposedly, Jesse James and gang came to the cabin and asked Mrs. Howell to cook up every chicken on her farm. She was worried her family would go hungry, but she didn’t dare to refuse. After they ate, the gang members thanked her politely and left. While clearing the table, she found a gold piece under each plate. The tale is in line with other Jesse James stories told throughout the Ozarks, and while it’s certainly possible they passed through here and paid handsomely for a meal, there’s no way to be certain.

That evening, I wander around the headwaters, including Montauk Spring, which issues about 50 million gallons of cold clear water every day. Downstream, the upper Current is a popular trout area. At 8:30 p.m., a loud horn sounds, which signals the end of fishing hours.

Waterside camp at Greer Spring. (Mike Bezemek)

The next morning, I drive downriver and walk a short path to Welch Spring, which bursts from beneath a cliff next to the ruins of an early 20th century convalescent hospital. The Howell-Maggard cabin is a half-mile downstream, across the river from a gravel access. Under normal circumstances, some friends and I had discussed paddling the river from Cedar Grove to Akers Ferry, which would have allowed for midday stops at the hospital ruins and historic cabin. But the pandemic disrupted our plans, so those explorations will have to wait until next time.

Regarding the James gang, in 1874, their route veered from Shannon County south to Bentonville, Arkansas. They reportedly robbed the Craig & Son store on Main Street, in a town better known today for Walmart and world-class mountain biking than bandits on horseback.

By this point, they had already evaded a sheriff’s posse raised shortly after the robbery. Now, the Pinkerton Detective Agency was following their tracks, which eventually led back to the James farm northeast of Kansas City. Needing evidence, the Pinkertons sent in a single undercover detective to pose as a farm hand. He was later found dead in a neighboring county.

There’s much more to the story after that, with the setting mostly shifting away from the Ozarks. The robberies continued, and more battles were fought between investigating detectives and the gang members, some of whom were killed. Frank eventually quit the life. Jesse went to New Mexico to recruit new members and was later murdered by one of them, Robert Ford, who sought reward money and fame. Throughout the saga, the trails usually led back to the family farm in Clay County, Missouri.

Over a century later, the St. Joseph Visitors Bureau created the Northwest Missouri Jesse James Driving Tour, with free brochures available online. Highlights include the Jesse James Bank Museum, site of the Liberty robbery; the Jesse James Farm and Museum, which offers guided tours; the Winston Train Depot, site of an 1881 robbery by the James Gang; and other relevant spots.

For me, the driving tour will have to wait. Once again, the pandemic foils plans, this time by closing the museums. But there is one site open, so I head north through rolling ridges to the northern edge of the Ozarks.

Legends say Meramec Caverns was once a hideout of Jesse James.

Upon arriving at Meramec Caverns, I have second thoughts about going inside. Legends (and marketing) say it was once a hideout of Jesse James. It’s possible. More concrete evidence reveals the cave was used by the Underground Railroad and, during the Civil War, by the Union Army to mine saltpeter to make gunpowder. Confederate guerilla forces dynamited the cave during the war, with some attributing the action to Quantrill’s Raiders.

But it’s mid-July and un-masked tourists are streaming into the cave. The news is filled with reports suggesting coronavirus spreads best in enclosed spaces. Sensing an ambush of viral particles, I decide to return another day. Without even stopping, I coast through the parking lot, flip a U-turn, hit the gas, and make my getaway like the James brothers.

Author: Mike Bezemek is the author and photographer of Discovering the Outlaw Trail for Mountaineers Books. The book combines stories from the outlaw era, including the exploits of Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch, with color landscape photos and a guide to adventures and hideouts along their historic routes.

Can’t wait to read the book! I have been studying my Family History during the Civil War, sometimes hard to tell which side was the most cruel. So many killed on just suspicion of being possibly an enemy from the other side.

What about Ozark County north of Theodosia. People have searched the caves there for years

Yes, u r right. My grandpa owned a lot of land in that area. He had some old buildings standing on a small part. My grandpa called it Jessie James town, also my dad talked that my grandpa knew Jessie and there was a cave that he would take food to when Jessie was hiding out there. There was some good fishing ponds also.

Just to let u know Jessie was not really shot and killed. He lived to be an old man and even a grandpa.

My relatives from Laurel and Knox county Kentucky have handed down a story. Some Wyatt’s moved from Kentucky to Missouri. Then the James Gange supposedly hid in the families house. A sheriff came and asked if they had seen any of the James Brothers. They said no. And very soon after moved back to Kentucky.

Have you during your research ever heard this story?

my grandfather told the story Jesse James hid ouy in his fathers barn

My great grandfather George Craig was a youth when the James Younger gang robbed his fathers store in Bentonville. His older brother described all the action including the way the robbers managed to escape the posse that chased after them George’s brother charley was in the posse. Years later after Jesse James was reported dead a man claimed to be James. No one believed him but my great grandfather who by then was a successful banker in port Arthur Texas. He was well aware of all the roads in and out of Bentonville since he was an avid hunter. He wrote the man who claimed to be James asking how he escaped the posse that night. The man knew all the right details including the creek where they managed to escape the hounds he also apologized for stealing his brothers boots.

That’s an awesome story! I live in Missouri, not too far from a lot of the places mentioned in this article and I’ve always found Jessi James’ story fascinating. From what I have read he was a product of the times and became a completely different man than he originally wanted to be. I hope this story is true and he was able to find some peace before he died.

My Great Grandmother Declue use to tell stories of how her parents hid the James gang out in their fruit cellar when she was a child. She said he was a very nice person.