“That was mean! I saw you throw that plant down the hill.”

Clink. Clink. Clink.

We’re all in a row, banging hand tools against the side of a cliff, swinging the handles up to our ears and sinking low into our knees on the downswing, carving out sections of dirt.

“What was I supposed to do with it?” I ask.

“Replant it!” someone chimes in.

I’d reluctantly tossed the fern down the hill to make room for more trail. I wanted to keep it, but Banjo said it was illegal.

They all clang at different tempos, the Pulaskis and McLeods, against the crumbling granite and roots on the clay hillside. Everybody is their own metronome, sweating out their own music.

“Obviously, my section of the trail is harder than yours.”

“No, I’m having the most difficulty-”

“It doesn’t matter, man.”

“Right, right.”

“OW! Christ.”

By 8:57 a.m., it’s already unbearably hot and we sound like angry chefs, banging pots and pans above the Black River. It’s mid-May and 85 degrees with 80-percent humidity. We’re on our third day of tread restoration on the Karkaghne section of the Ozark Trail (OT).

The Americorps crew, made up of all boys in their 20s, argue amongst themselves between ax swings. They were hired to do trail maintenance today. Their names are Austin, Isaiah, Banjo, J.P., and Kalan.

“Have you guys seen ‘Ready Player One’? That’s a sick movie.”

“Ready Player One’ is just a copy of ‘Spy Kids’.”

“Oh, 100 percent.”

“‘Ready Player One’ was a good movie, but ‘Spy Kids’…eh, negative.”

“What’s wrong with ‘Spy Kids’?”

“You guys have a problem with Taylor Lautner?”

“Dude, that guy was in ‘Shark Boy and Lava Girl’, not ‘Spy Kids’.”

“Ohhhh.”

“Come on, man.”

****

I’m a first-time volunteer, toiling alongside the Americorps crew and the khaki-clad Ozark Trail Association (OTA) volunteers. I’m here to give back to a trail in my home state, keeping a promise I made to myself after hiking a long section of the Appalachian Trail.

Two long-time OTA volunteers in their 70s, Leatris Studer and Bruce Hadley, stop working for a moment to examine a large boulder in the middle of the trail.

“It might slip one of these days and topple down the trail,” Studer says.

“We’re not going to do that today,” Hadley says, shaking his head.

“It would take dynamite to get it out of there,” Studer says.

OTA Construction Manager Terry Hawn brushes past us, sweating bullets in his highlighter yellow shirt. He carries his hand tools 500 yards past us to begin a new 10-foot section of the trail after just having finished another alongside us.

Last night at the Sutton Bluff campground, he’d learned that OTA President Kathie Brennan wasn’t going to be able to make it to this trail maintenance event. Afflicted with tick diseases and the fatigue that comes with them, Brennan made the decision to stay home. She almost never misses an event.

Apparently, tread restoration is the hardest kind of trail maintenance for a first-time volunteer. It feels like gardening for seven hours straight. I’m enthusiastic, though, and take to it right away, making the Americorps crew nervous. I can’t appear as though I’m more into it than they are.

“I’ve got the truck pulled up pretty close to the trail,” Hawn announces. “I’ve got cold drinks and a pack of Gatorade in there when everyone is done.”

Our goal for this trail maintenance event is to widen the trail, re-establish the backslope, and maintain the critical edge of the trail for runoff. The event is funded by the Forest Service’s Great American Outdoors (GAO) Act.

The OTA earned $149,000 from a GAO grant in 2021. Soon, it will have to submit another proposal for renewal. The OTA manages the maintenance of nearly 430 miles of the Ozark Trail. The trail is designated as a National Recreation Trail and runs through the St. Francois Mountains and Mark Twain National Forest.

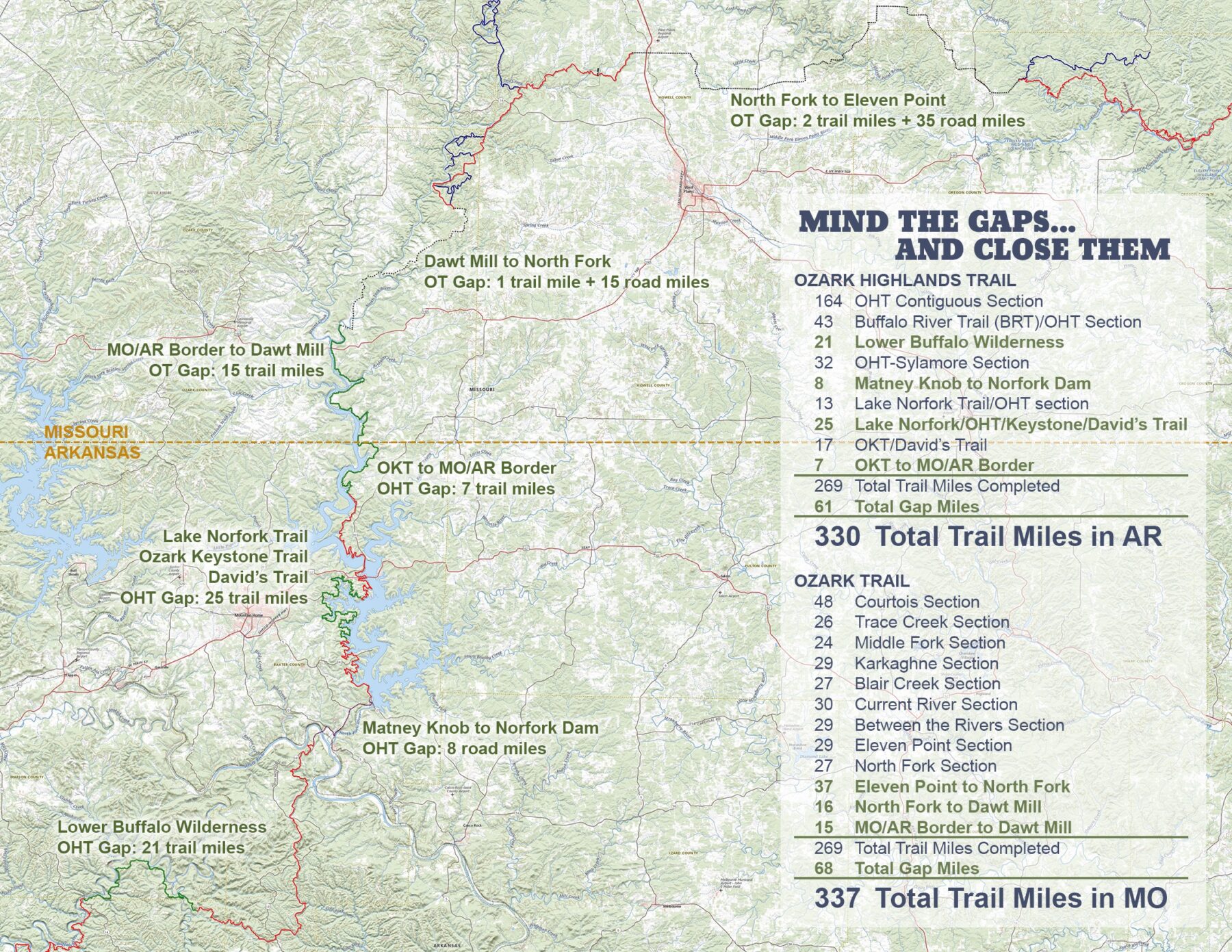

The southernmost tip of the OT hovers about 40 miles from the Arkansas border, and since the early 2000s, there has been sporadic interest in connecting the OT in Missouri to the Ozark Highlands Trail (OHT) in Arkansas. If this were to happen, the combined trails would be named the Trans Ozark Trail.

****

Around 10:00 a.m. I lean against the hillside and rest my head on a pile of leaves.

“You’re gonna get ticks,” Issiah tells me.

I shrug, too tired to care. I have permethrin and DEET on my side.

I think about the day before, wading through the Black River in my shorts after our work day. The water was no warmer than 65 degrees — perfect after a long day in the heat. The water was crystal clear, revealing a riverbed of quartz, chert, and mozarkite. Isaiah caught a slow-moving fish in his hands, a bleeding shiner. It had a full face of makeup on and swam away slowly.

I realized it was injured.

“That’s the only way you were able to catch it in your hand, wasn’t it?” I’d said.

“Yes.”

We wouldn’t have seen its red cheeks and charcoal eyeliner otherwise.

I get up from the pile of leaves, suck on a Jolly Rancher to quench the back of my throat, and continue swinging at the dirt. After creating a 3-foot-wide corridor on flat ground, I push the excess forest matter off the trail using the McLeod. I patter my feet on the ground to tamp the dirt, just like a barista would compress coffee grounds to make an espresso shot.

I smile. The trail already feels better beneath my feet, more spongy, easier on the knees. I can see the results of a day’s work immediately.

****

The late John Roth, who organized the OTA in 2002, envisioned a continuous footpath from Missouri to Arkansas that would stretch over 700 miles. Since the association managed to complete the Upper Current River section in just a few years, it would seem that building more of the OT to the Arkansas border would be doable.

But, according to longtime OTA members, Roth’s vision started to shift focus in 2006. Instead of searching for new land to build a continuous footpath, he decided to focus his efforts on maintaining the current trail and creating spurs.

Ozark Trail blaze. (Mark Nettles)

“We kind of got burned when we did the Upper Current River section because we ignored other parts of the trail that needed attention,” said Hawn. “We don’t want to neglect other parts of the trail at the expense of a new project, so we are taking it slow.”

The southernmost build the OTA has organized so far has been in Udall, Missouri.

Last year, there were plans to host a golden spike event as a formality, marking a small parcel of land as being shared by the OT and OHT, but the plans were canceled due to the pandemic. As of right now, neither the OTA nor the Ozark Highlands Trail Association (OHTA) has made efforts to begin the build to connect the two trails.

“Some people want to have a golden spike event to kick off the build and some want to do it when we finish the build. It’s about 50/50 right now,” said Hawn. “I’d like to draw in some politicians for support and funding. It’s probably not going to happen this year, but I’m not saying it could not happen next year.”

****

As of right now, there’s not a lot of public land left in southern Missouri on which to build a trail. To complicate matters, some private landowners in the region aren’t even aware of the OT’s existence, nor the effort to connect it and the OHT.

Still, Chief Sawyer and OTA Vice President Mark Goforth is in favor of an OT-OHT connection using a respectful mix of private and public land. “We need more easements and more landowners to allow us more access,” he said. “However, we don’t want to go through someone’s field or backyard.”

According to Brennan, there should be a separate entity formed to manage the Trans Ozark Trail if and when the two trails ever connect. The OTA is managed by one paid employee and a board made up exclusively of volunteers, so their labor is already stretched to the max.

Brennan and Hawn manage all the volunteers for the OTA, including trail building and trail maintenance events. The objective of the volunteer events is to make a group effort to care for the trail and maintain it so that hikers, bikers, and horseback riders can enjoy a safe, open corridor of trail. Common forms of routine trail maintenance include lopping overgrown tree limbs, weed eating, and tread restoration.

Brennan and Hawn started out hosting just two volunteer mega events, one in the spring and one in the fall. However, they now run volunteer events from Labor Day until late May or early June, even volunteering in freezing temperatures during the winter months. Hawn and Brennan used to work eight months out of the year but now work about 11, juggling events, grant opportunities, and outreach efforts.

****

In order to build more sections of the trail, the OTA needs to maintain and build its volunteer base, especially in southern Missouri. Currently, the majority of volunteers commute from St. Louis. The OTA would like more volunteers from Springfield to attend regular trail maintenance events in the Ozarks.

The bigger events in southern Missouri draw, at most, 30 volunteers. Hawn worries that higher gas prices could deter St. Louis volunteers from driving to the southern sections of the OT.

According to Beth Little, an OTA volunteer who has attended more than 20 of the organization’s trail maintenance events, neither distance nor gas prices will deter her from volunteering. Little is also in favor of the OT-OHT connection.

“You could walk from one end of the state to the next, and you could do the whole Ozarks. They’re so different from where they start to where they end,” she said. “You have the Appalachians, the Continental Divide, and the Pacific Crest Trail. Those are all landmarks that have their own trail. To have that for the Ozarks would be pretty cool.”

Hiking the Ozark Trail.

OTA volunteer George Lipscomb has been actively volunteering for six years and has attended more than 25 trail maintenance events. He stated that a rise in gas prices would not keep him from volunteering either and that he would be happy to work on building trail to connect the OT and OHT.

A longer continuous trail in the Ozark region could increase tourism revenue in the areas the trail runs through, similar to the Appalachian Trail, where hotels and restaurants get thru-hikers and section hikers as customers.

“I think it’s not only beneficial locally but it’s also attractive on a national scale, getting notoriety for the Ozark Trail. It exposes hikers and users to different topography and geography. Local businesses are able to take advantage of it,” Lipscomb said.

Another potential hotspot for tourism revenue would be near Norfolk Lake, where trail construction is currently underway. It’s a mixed recreation use area for fishing and hunting, so planning the hiking trail strategically around the other activities is at the forefront of the OTA’s mission.

Brennan is also interested in eventually seeing the OT gain countrywide notoriety and possibly earn the designation of a National Scenic Trail, like the Florida Trail or Arizona Trail. This would draw more awareness, hikers, members, funding, and volunteers. (The annual individual membership fee for the OTA is $35, which helps fund maintenance and construction projects.)

According to Abi Jackson, the only paid employee and chief operations manager of the OTA since 2009, the opportunity to volunteer presents a unique experience for people to come together in community.

“Kathie does a great job. She’s so friendly and welcoming. All our volunteers are like that. It’s a good weekend for people to get outdoors, get a free weekend of camping, and meet some like-minded people,” Jackson said.

However, in order to manage a larger number of volunteers, the OTA would like to train more crew leaders to direct volunteers and Americorps crews during trail maintenance events. The most progress it has made in one day is building a full mile of trail in the Upper Current River section through a mega volunteer event with 200 volunteers.

****

Hawn, a native of Farmington, Missouri, makes sure to take care of the volunteers during trail maintenance events.

“We don’t pay them. We make them sweat pretty bad. They enjoy getting sweaty, dirty, and working hard,” he said. “A tradition that John Roth started was cooking for volunteers. It’s the way things are done in the South. If someone walks in your house as a guest, the first thing you do is offer them something to eat.

“[Cooking for the volunteers is] our way of saying thank you. The stories that come out of having dinner together are funny and help build connection, help build community. Those are the kinds of connections that Kathie and I like to try and keep,” Hawn said.

The OTA uses some of its funds to pay Americorps $85 per day per person to help maintain the trail. According to Hawn, these workers are valuable trail builders because they have strong backs and already have experience with chainsaws and other hand tools. If the OT were to extend down to Arkansas to connect to the OHT, the Americorps crews from St. Louis would be an integral part of that build alongside OTA volunteers.

****

Jackson Rhoades and Becca Martin are in charge of the Ozark Keystone Trail (OKT). The OKT is also known as the Ozark “Konnector” Trail because it would be used to connect the OT and OHT in the future. According to Rhoades, the word “keystone” is about “connecting the two magnificent trails.”

David’s Trail makes up a portion of the OKT and currently serves as a recreational and educational trail in Mountain Home, Arkansas. The OKT is 20 miles long at present, and there are plans to expand the trail 10 miles in either direction. Rhoades’ biggest advantage is having large, mechanized equipment for building trail on hillsides and bluffs.

“With sufficient funding, we’ll get to the Arkansas-Missouri state line within the next six to eight years. If the funding continues, we’ll continue north. If the funding isn’t there, we’ll drop south and work on connecting to an existing trail on the Arkansas side,” Rhoades said.

Rhoades and Martin are in contact with the OTA and OHTA to communicate the presence of the OKT while they apply for grants to get construction funding. The machines that Rhoades uses to build trail could be invaluable to making progress toward a connection.

The OHTA would also like to recruit more volunteers to maintain sections of the trail, especially on the eastern portion of the trail. OHTA President Phil Brown is in favor of the OT-OHT connection. However, retired people are more likely to volunteer on the trail because they have more time on their hands than young and middle-aged adults. He’s worried about the longevity of the organization if younger people don’t get involved.

“We want to build membership and develop a sense of ownership. We want to bring in younger members. If you look around the room, you see a lot of older people, and that does not bode well for the existence of our organization,” Brown said. “But I’m working on it.”

****

For there to be a continuous footpath called the Trans Ozark Trail, both the Ozark Trail and Ozark Highlands Trail would need to close some gaps. The biggest hole to close on the OT would be the 30 miles between the Western terminus of the Eleven Point section to the new Norfolk section. The next it could close would be the 8-mile gap to Dawt Mill Resort.

The OHT currently has less breaks to fill than the OT. In the next two years, the only section of trail the OHTA will need to finish is a 17- to 23-mile gap with the permission of the Parks Service.

“We don’t have the obstacles that the OTA has, as most of our trail is completed and is on Forest Service land. Our biggest obstacle is working on the trail between Lower Buffalo Wilderness and Dillard’s Ferry,” Brown said.

The main obstacles in creating the Trans Ozark Trail on the Missouri side are finances, land management, and the number of volunteers available for work days. Although Brennan hates asking for money, the OTA does have a designated fundraising coordinator. In the future, it would like to set up an endowment like the OKT has. The OTA would need $25,000 to start and it would take one year to set up.

“We’ve operated on pennies. We’re pretty good about finding the best deal and being transparent about our spending,” Brennan said.

In addition to finances, if the OTA could find land to build on, it would have to submit a NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) proposal to the federal government detailing the potential environmental impacts of the trail on the land. NEPAs can take two to four years to get approved.

****

Dave Tobey, an Eminence, Missouri, native and kayak tour guide on the Current River, served as an OTA board member for six years. He provided an interpretive float from Pulltite Spring to Round Spring for Americorps and OTA volunteers after a trail maintenance event last June. The event gave the volunteers a chance to relax and learn about the history and ecology of the region where they helped maintain the Ozark Trail.

Tobey is confident that Brennan and Hawn will be able to lead the OTA to make the OT-OKT connection.

“Kathie Brennan is such a driving force. They’ll get it done. That will make the Ozark Trail and Ozark Highlands Trail a significant trail for serious hikers, and it’ll be wonderful when it’s done. I can’t say enough good things about the Ozark Trail Association and its volunteers,” Tobey said.

Hawn is a little more skeptical that the connection will happen in his lifetime. He’s not sure how many years it will take because it’s hard to predict what private landowners will wish to do — and the land could potentially change hands multiple times, disrupting relationships between the OTA and stakeholders.

The laws for land easements also recently changed, which creates an unstable future for the OT potentially running through private land.

Hawn, who is retired himself, performs manual labor on the trail alongside volunteers at nearly every volunteer event, even with a knee injury and seasonal allergies.

“My days are numbered physically. Unfortunately, I didn’t start this early enough. It’ll be someone else’s joy to rejoice if they get [the OT-OHT connection] done,” said Hawn. “I’d love to see it in my life, but I won’t be building at that time.”

Author: Aurora Blanchard is a contributor to Terrain Magazine.

Leave A Comment