A couple of years ago, I spent two days cycling on scenic, quiet roads in the Boone’s Lick Country of central Missouri. This region along the Missouri River was a destination for settlers seeking fertile land and became a waystation for westward expansion. I’ve wanted to explore more of the territory and history here ever since and ride more of the gravel roads.

In the early 1800s, Boone’s Lick Road was the main route from St. Charles to Franklin. The road’s name came from Daniel Boone’s sons Nathan and Daniel Morgan Boone, who expanded a Native American trace to reach a salt spring or “lick.”

From the end of the road in Franklin, William Becknell departed on September 1, 1821, on a trading expedition to Santa Fe. Deep in debt at the time, he left for the 800-mile journey with $300 worth of trade goods loaded on pack horses. He crossed the river near a limestone bluff known as Pierre a Fleche, meaning Rock of Arrows, from which Native Americans used stone to point their arrows.

Becknell’s investment paid off when he returned four months later with $6,000 in silver coins. He went back to Santa Fe the next spring, changing the route so he could haul the goods in wagons instead of on pack horses. The second trip netted him $91,000 and recognition as the “Father of the Santa Fe Trail” for blazing a successful wagon route.

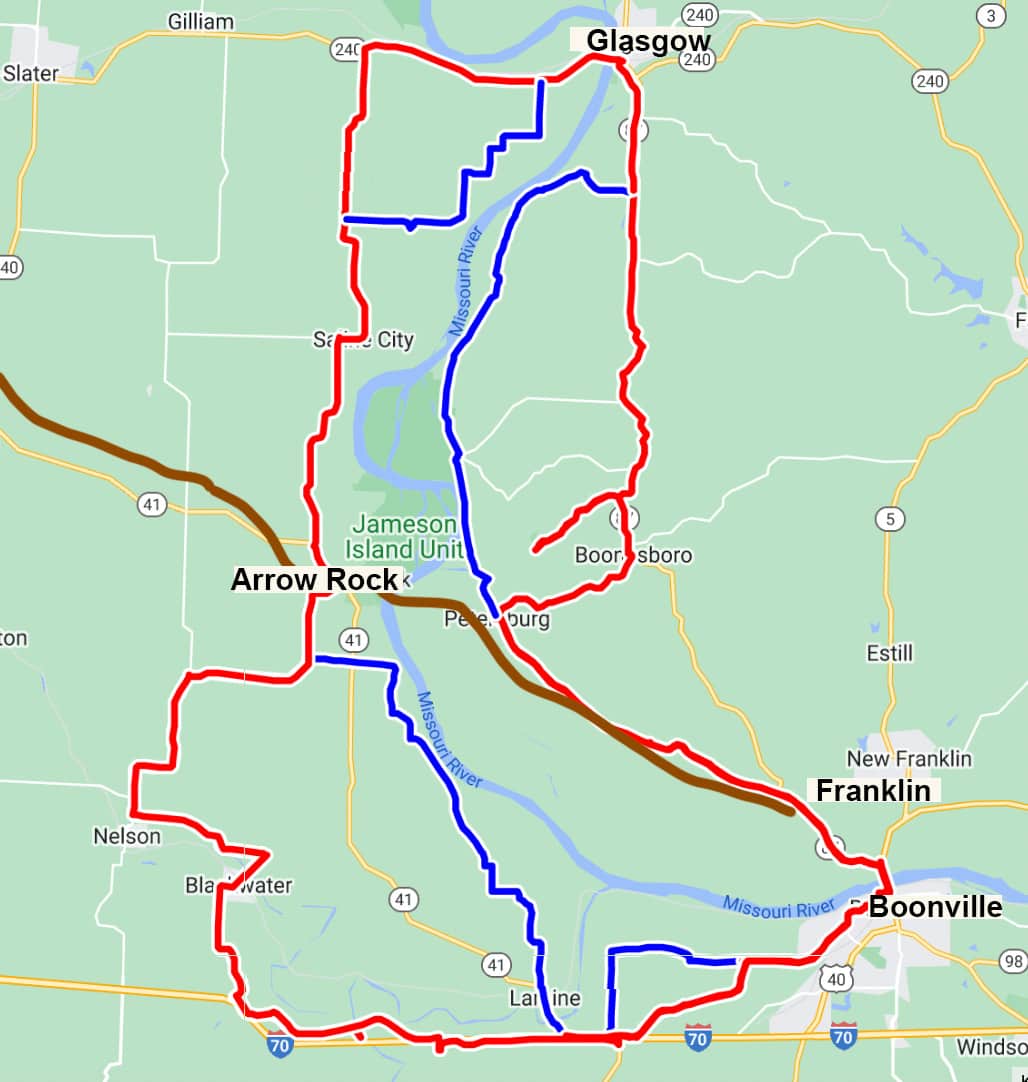

The Missouri Bicycle and Pedestrian Federation has published both paved and gravel routes in this area. The roads circle around the first 10 miles or so of the trail, from Franklin to where Becknell’s party crossed the Missouri River to Arrow Rock. The ferry there is long gone, but there are road crossings in Glasgow and Boonville.

Missouri Bicycle and Pedestrian Federation’s Santa Fe bike routes.

My adventurous friends Lois McBryan and Janice Rifkin are joining me for this weekend of exploration on two wheels. Both experienced cyclists, they haven’t done much gravel riding beyond the crushed stone on the Katy Trail but are game to give it a try.

On Saturday morning, the mercury hovers in the mid-30s with a stiff north wind — a bit chilly but we figure a cold ride is better than no ride. We make the best of it by dropping a car in Franklin and riding back from Glasgow on the east side of the river with the wind at our backs.

Settled in 1836 by merchants, Glasgow grew up on wealth from hemp and tobacco plantations. For a town of just over 1,000 people, it has a lot to offer visitors — a grocery store, bakery, four restaurants, a winery, antique shops, and two bed and breakfasts — and has stories to tell from the Civil War and the railroad expansion era.

On Market Street, we walk by Lewis Library, a striking two-story Italianate brick building. The library was built in 1866 with a bequest from Benjamin W. Lewis, a wealthy plantation owner. Lewis served as a Union Army Colonel during the Civil War and freed his slaves in 1863. After the Battle of Glasgow in 1864, he was brutally tortured and beaten by the Confederate guerrilla Bloody Bill Anderson. Before he died 16 months later from his injuries, Lewis left $10,000 in his will to build a library, a rare gift for a midwestern town in the 19th century.

* * *

By 11 a.m., the temperature has risen all the way up to 39 degrees, as good as it will get for our ride. On the way out of town, we pedal in the shadow of a railroad bridge built on the site of the 1879 Glasgow Rail Bridge — the first all-steel bridge in the world.

We warm up on a couple of steep hills on Missouri 87. Then, the road levels off. Traffic is light, and the wind pushes us along. The views of the rolling country are tall and wide. Settling in, we ride toward Boone’s Lick State Historic Site.

Soon after we turn right on Route 187, three muscular hounds come charging out. Lois is prepared. She gives them a loud blast on her whistle, which stops the dogs in their tracks like magic. I’ve heard of this tactic, but this is the first time I’ve seen it in action.

The author cycling on Missouri 87 in Boon’s Lick Country. (Janice Rifkin)

At Boone’s Lick State Historic Site, signs tell the story of the salt works that operated here in the early 19th century. Salt was essential on the frontier for preserving food and tanning hides. Nathan Boone found salt springs here while returning from a hunt in 1804. The next year, he and his brother Daniel partnered with James and Jesse Morrison to build a salt works at the springs.

A half-mile hike leads down to the saline creek. According to archeological evidence, salt water was boiled away in furnaces that were built in pits six feet deep and 30 feet long. The furnaces burned up to three cords of wood a day to boil brine in 30 kettles. One kettle of brine yielded a bushel and a peck of salt, or about 60 pounds. Dugout canoes and keelboats carried the salt downriver to St. Charles, where it sold from $2 to $2.50 per bushel.

* * *

From the Boone’s Lick site, we turn west on the first gravel road of the day. Janice’s e-bike skids on the rocky surface at first, but after turning off the pedal assist to slow the bike down, she has an easier time. We descend to the fertile bottomlands of Petersburg, where the gravel isn’t as chunky, and the going is easier. On the lonely roads, I imagine how it might have felt to travel here 200 years ago.

As we turn east on Route Z toward Franklin, the north wind chills the left side of my face, a reminder of what a break we’ve had today riding downwind. We load up the bikes in Franklin, where William Becknell started his trail-blazing expedition, and drive back to Glasgow to pick up the other car. On the west side of the river, we take Route P south to Arrow Rock. The road is deserted here, and the hills look like fun.

The town of Arrow Rock was organized in 1829 to supply the wagons that crossed on the ferry. Steamboats landed here, bringing passengers bound for the Santa Fe Trail and carrying away hemp and other produce to the southern states. The riverfront trade propelled Arrow Rock to become the busiest port between St. Louis and Kansas City.

J. Huston Tavern in Arrow Rock. (Janice Branham)

The entire town is a National Historic Landmark, and we dine that night at the town’s centerpiece, J. Huston’s Tavern. Built by Joseph Huston in 1834, the tavern provided food, lodging, and supplies for travelers on the trail. Here, a kitchen with 19th-century furnishings demonstrates how meals for travelers were prepared. Upstairs, a ballroom and sleeping rooms are on display.

* * *

Sunshine returns on Sunday morning for our hike through Arrow Rock State Historic Site. Behind the visitor center, we find Big Spring, where travelers on the Santa Fe Trail filled their water stores. Nearby, the River Landing Trail leads to the Lewis and Clark Trail of Discovery.

The trail runs through the bottomland forest in the Jameson Island Unit of the Big Muddy National Fish and Wildlife Refuge to the Missouri River. Here the river is wide, shallow, and filled with sediment and snags.

When the Corps of Discovery passed here in June 1804, William Clark wrote of the “disagreeable and Dangerous Situation, particularly as immense large trees were Drifting down and we lay immediately in their Course.”

Shipwrecks are buried in the bottomland. Some were casualties of strong currents and hidden logs. Others were lost to exploding boilers clogged with sediment from the river.

Arrow Rock Ferry Landing site. (Janice Branham)

The north end of the trail ends at the Arrow Rock Ferry Landing site. It’s now high and dry since the river slowly shifted to the east. From the ferry landing, we walk by some of the historic homes built in the town’s heyday.

After my friends head home, I take off to ride the gravel south of town on Arrow Rock Road. The wind is behind me again, the sun is warm, and all is quiet in the farmland. In 12 miles, only two cars pass me, and one dog quietly ambles out to see what’s up. The scene is just the kind of Zen experience I’d hoped for.

On the way back north on Missouri 41 there’s a headwind and more cars, but they change lanes to pass me. A longer, quieter route north goes through Blackwater a little further west of M0-41. I’ll have to come back and try that way the next time. There’s more territory to ride, and more to learn in Boone’s Lick Country about Missouri’s history and role in the country’s westward expansion.

Route Finder

To download the Missouri Bicycle and Pedestrian Federation’s Santa Fe Trail bicycle routes, go to mobikefed.org and look under Missouri Bicycle & Touring Routes for “Birthplace of the Santa Fe Trail.”

Author: Janice Branham is a regular contributor to Terrain Magazine.

Top Image: Lois McBryan and Janice Rifkin on the Sante Fe Trail. (Janice Branham)

Leave A Comment