Women are not small men.

This is the key argument in exercise physiologist Stacy Sims’s 2016 book Roar: How to Match Your Food and Fitness to Your Unique Female Physiology for Optimum Performance, Great Health, and a Strong, Lean Body for Life.

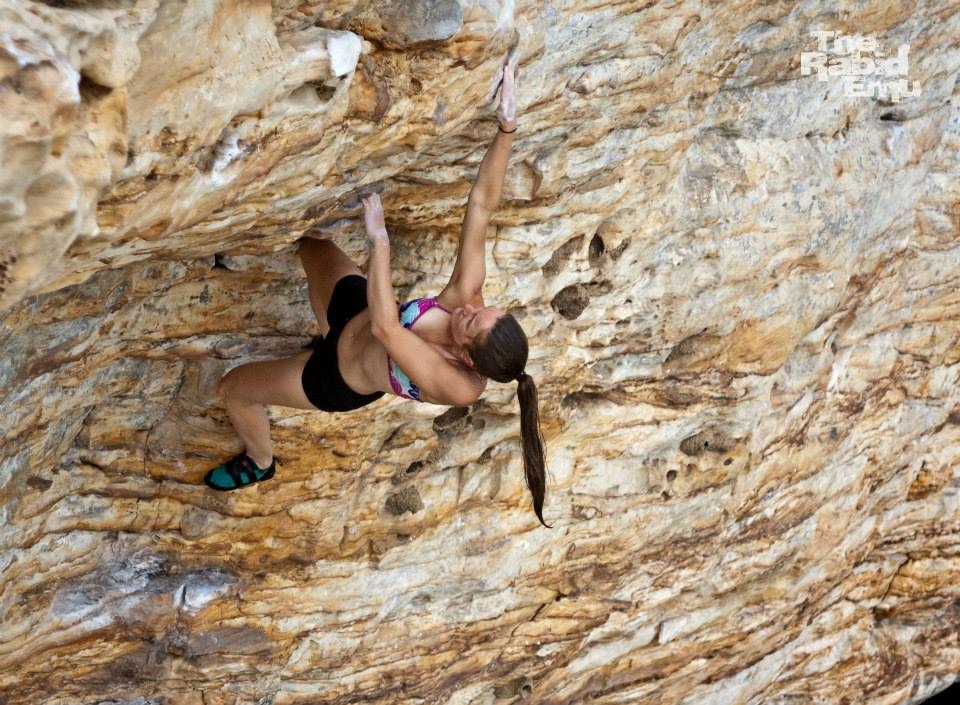

Recreational climber and St. Louis resident Natalie Rolwes can attest to this. “My partner was a male and a far more seasoned climber. He used to give me beta [intel] for routes he’d already sent. Sometimes it was helpful, but often I’d try the moves the way he did them and they’d feel impossible,” she said.

Sure, women differ from males in obvious ways, like flexibility and strength. But female athletes face less apparent obstacles that even scientists don’t always understand. This is due, in part, to research bias. Science News Magazine sampled 188 sports science studies from early 2015 and found that only 4 percent were specific to female athletes, compared to 27 percent that focused on men.

Still, studies (mostly small) have shed some light on how female anatomy and physiology affect exercise performance. Here are six issues that many female athletes face, plus tips to overcome them.

Periods

Let’s just get this one out of the way first. A hard workout may be the last thing you feel like doing when you have your period. Hormonally, though, it can be a great time to push yourself.

Case in point: Paula Radcliffe’s world record performance at the 2002 Chicago Marathon was on the first day of her period.

Scientific studies on sports and the menstrual cycle are conflicting, although there’s some evidence that strength and endurance are higher during menstruation than in the days before your period.

If you notice a pattern of fatigue during certain parts of your cycle, you may want to adjust your expectations or your training. These might not be the optimal times to, say, attempt a one-rep max back squat.

Journaling your workouts, your periods and your rate of perceived exertion for a few cycles may help shed some light on whether hormones affect your strength and stamina.

Above all, don’t let hormone changes psych you out.

“I tried to put it out of my mind and not let it become an issue. It’s one of those things that can become a bigger issue if you let it,” Radcliffe told reporters from BBC Sport about racing during her period.

Injury Risk

Studies have found women to be an average of 3.5 times more likely than men to sustain non-contact ACL injuries. Anatomical differences account for some of this discrepancy, but hormones may play a role as well.

Ligaments tend to loosen during pregnancy due to the hormone relaxin, which softens the tissues in preparation for birth. The resultant looseness (known in the medical field as laxity) makes joints more vulnerable to injury.

Research also suggests that the hormones estradiol and progesterone influence laxity in premenopausal women. Some studies have found increased knee laxity compared to men when these hormones are higher, although this is somewhat controversial.

Risk is also believed to be higher during menopause.

“When menopausal, the ovaries do not produce any more estrogen and produce minimal testosterone,” said Holly Hiroko Kodner, MD, an OBGYN at Balanced Care for Women in Creve Coeur, Mo. “With less estrogen, there is more fragility to our blood vessels, connective tissue, muscles, tendons and at a higher risk for injury. Also, with less testosterone, there is less building of muscles. However, that does not mean one should not exercise, one should just be more careful.”

Regardless of life stage, it makes sense to incorporate exercises to protect your joints.

“Training your body to balance and respond to different terrains, surfaces, movements and other factors is ideal,” said Tyler Bryant, MS, DC and lead clinician at InBox Functional Rehab in Clayton, Mo. He recommends single-leg balancing exercises and strengthening exercises for the gluteus maximus, hips and intrinsic foot muscles.

It’s also best to address any consistent joint pain early on, before it becomes a bigger problem.

Body Heat

It’s well known that hormones cause hot flashes in menopause. But hormones may also affect body heat for premenopausal women.

Core temperature increases after ovulation, when progesterone is on the rise. This not only increases likelihood of overheating but also contributes to fatigue. Some studies have suggested that progesterone may further delay the sweat response, although a 2013 study found that proper hydration likely offsets this delay and promotes cooling.

A little planning can help enhance safety and comfort during activity, particularly when it’s hot. It’s important to take in enough fluids before, during and after activity. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) suggests 16 to 20 ounces of fluids four or more hours before activity, with 8 to 12 additional ounces 10 to 15 minutes before you get started. The ACSM has also recommended an average of 12 ounces of fluid for every 30 minutes of exercise, although this may vary based on intensity and other factors.

Water is fine for workouts less than 60 minutes, but sports drink consisting of no more the 8 percent of calories from carbohydrate is recommended for efforts greater than an hour. Women who are well-hydrated at the beginning of an event can often drink to thirst, provided they are taking in at least 14 ounces per hour of activity. Menopausal women may find it helpful to stick to a strict hydration schedule due to a decreased sense of thirst.

Other steps can be taken to lower body temperature before, during and after exercise. Whenever possible, sit in a cool place pre- and post-workout. Cold beverages or popsicles can help bring down core temperature a bit, while those prone to overheating may benefit from a cooling vest. Try to route your path near streams, fountains or sprinklers when running or cycling, so that you can splash off. Cooling towels are a good option during races or other events.

Finally, pregnant women need extra fluids and should be especially cautious on warm days. “I advise all of my pregnant clients to take frequent water breaks, move at a slower pace and always stop if they are experiencing any signs of dizziness, nausea or other similar ailments,” said Jenni Haug, founder of Magnolia Fitness in Shrewsbury, Mo.

Incontinence

It’s an uncomfortable topic, but women are more prone to leak urine during exercise. Urinary incontinence is more common during and after pregnancy and in menopause, but it can happen to anyone. In fact, a 2012 study found that it affects one in eight young women without children.

A urogynecologist or pelvic floor physical therapist can help treat the condition. Pads or specialty undergarments may reduce discomfort. Emptying your bladder before exercise is also recommended.

Pregnancy

Pregnancy is certainly not the time to go for a speed record or take up heavy deadlifting for the first time. But exercise while pregnant can lay the groundwork for an easier return to fitness postpartum.

“Hip and pelvic stability training is very important to reduce lower back pain, and to help recover from childbirth quickly and limit complications postpartum,” said Bryant.

A few adjustments may be needed for safety and comfort. Simple changes like wearing loose clothing can help. A belly support band can minimize hip and back pain, particularly in sports that involve bouncing. Strength training routines should also be adjusted.

“I always tell my patients it is so important to maintain physical strength and flexibility. The goal is not to build, though, but to maintain,” said Hiroko Kodner.

Movement substitutions — such as standing crunches instead of supine ab work — help safely maintain strength. Modifications like these can also help prevent diastasis recti, a separation of the rectus abdominus muscles that can cause weakness, instability, and pelvic or lower back pain. A 2016 study found that 60 percent of moms have it six weeks after childbirth.

And of course, there’s nutrition. Even sedentary moms need an average of 340 extra calories per day during the second trimester and 450 extra calories per day for the third trimester. As an athlete, you probably need more. Speak with your doctor if your weight gain is slow, especially beginning in the second trimester.

Postpartum

Postpartum exercise is helpful for weight loss and in boosting mood. Most new moms require a few weeks off before they’re medically cleared to resume exercise. Many would call the first few workouts humbling.

“I will NEVER forget my first attempt at running after the birth of my first kid,” said Sarah Plumb, a marathoner, swimmer, Ironman finisher and mother of two from St. Louis. “My expectations were low, and still it was rough.”

In addition to temporary losses in stamina and strength, nursing moms may face aches and pains like sore breasts. Wearing a highly supportive bra during exercise is key. It’s also helpful to nurse or pump your breasts before engaging in exercise. You may need to manually express milk or pack a manual pump for endurance events when you can’t nurse.

Also be sure to fuel properly. Exclusive breastfeeding burns an average of 300 to 500 calories per day, and you’ll need extra calories based on activity intensity and duration. You may not be eating enough if you feel drained, or if baby isn’t gaining weight or producing enough dirty diapers in a day.

Above all, listen to your body and don’t get discouraged.

“Once my body remembered what to do, I was back at it in no time,” said Plumb, who set a personal record at the Chicago Marathon just eight months postpartum. “I’m certain things fell into place more quickly because of the base I’d built up during pregnancy.”

Female Advantages

If some of this seems like gloom and doom, keep in mind that ladies may have an athletic advantage in a few situations.

Studies have shown that women use more fat for fuel than men during prolonged exercise. This may translate to better endurance in longer events.

And speaking of fat, women have a higher body fat percentage than men on average. A 2010 Harvard Health Letter reported that subcutaneous (under the skin) fat protects against cold temperature. In theory, this could give women a comfort advantage in cold weather sports like snowshoeing.

Many women I spoke with also reported that being a female athlete builds mental strength and creativity. Instead of throwing in the towel on tough climbing routes, Rolwes came to rely on precision and flexibility rather than upper body strength. And consider American Ninja Warrior contestant Kacy Catanzaro, who found creative solutions to conquer the course at just 4’11” and 95 pounds.

Finally, nothing is holding us back! A 2016 report by the Outdoor Foundation found that women are participating in outdoor activities nearly as much as men. In fact, women ages 18 to 24 are more active outdoors than their male counterparts. This means we have a new generation of badass female athletes to follow and encourage.

Author: Kimberly Yawitz is a regular contributor to Terrain Magazine.

Leave A Comment