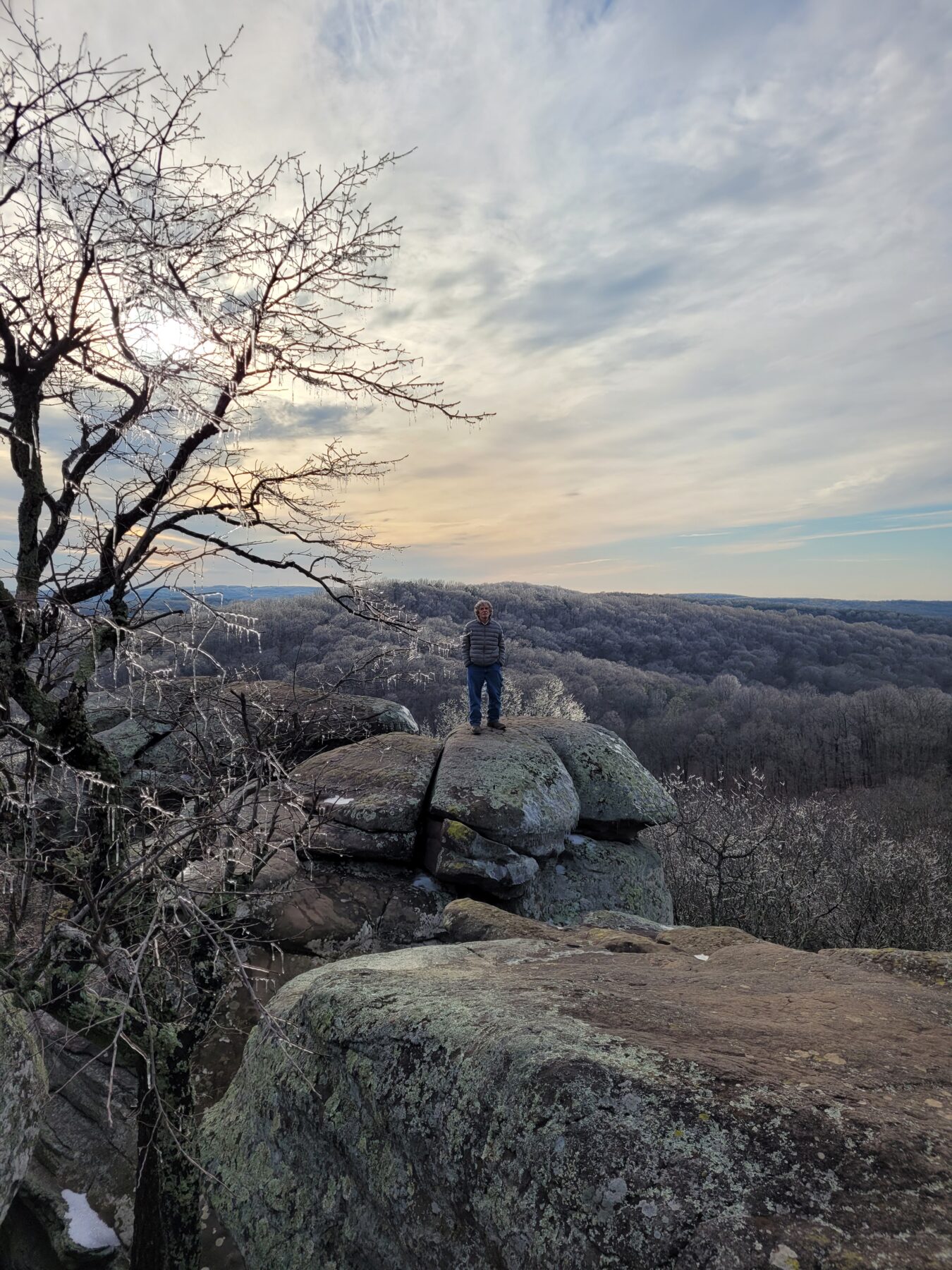

A 90-minute drive from St. Louis will land you at the northwestern edge of the wonder and majesty of Shawnee National Forest, a 289,000-acre playground of tall pines, oaks, and hickories that is dotted with hiking, camping, biking, and kayaking opportunities. Beautiful vistas like Garden of the Gods and its ancient rock formations entice people to return again and again to this gem in southern Illinois.

Yet in the midst of this idyllic setting, a battle is brewing. The US Forest Service is promoting logging sales in certain sections of the forest, and some residents in the area are trying to stop them. They say the federal agency seems to serve loggers rather than park users and that efforts to rejuvenate the logged areas are halfhearted at best, resulting in fields of low brush and invasive species, with few trees.

A new documentary film called Shawnee Showdown: Keep the Forest Standing outlines the increasing number of logging projects being pursued by the Forest Service. In her film, producer Cade Bursell, a professor at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, tells the story of activists in the 1980s and 1990s who protested clear-cutting and burning of the forest. In 1990, they staged a 79-day “showdown” at a logging site, camping out and some chaining themselves to logging equipment for dramatic impact.

An activist during a 1990 standoff in Shawnee National Forest. (Orin Langelle)

People were arrested and the group finally left, defeated. The trees came down. But in 1996, due to public awareness and lawsuits, a judge issued an injunction that prevented most types of logging and burning in Shawnee National Forest.

For 17 years, the injunction stood. But in 2013, logging resumed when a judge lifted the sanctions. The Forest Service had given the court a revised forest plan for “ecological restoration” of new areas to be logged. The agency said it was moving away from clear-cutting and instead using a less drastic technique called shelterwood, in which mature trees are left standing to provide shelter in which saplings can grow. The agency also planned to employ thinning to allow more sunshine in, so that oaks could thrive in the mostly pine forest.

Oaks are important, the agency argued, because they provide a steady supply of acorns to wildlife and a rich understory to many species of plants and insects.

Activists Back at It

John Wallace was one of the guys who chained himself to a piece of logging machinery in 1990. Reporters referred to the activists as “hippies.” A mild-mannered resident of Simpson, Illinois, which is on the eastern part of Shawnee, Wallace is a thoughtful, articulate defender of the neighboring forest.

He closely monitors the various timber sales and believes the Forest Service is still allowing logging companies to do clear-cutting under the guise of “ecological restoration.”

A recent visit to several logged areas revealed empty clearings with a few remaining stumps and downed branches. No trees appeared to have been spared.

“The damage inflicted is very similar to clear-cutting,” Wallace said. “It’s a shame. I wish they would just tell the truth.”

Wallace, who holds a bachelor’s degree in plant and soil science, says there is no evidence that logging and burning encourage new oaks to take root. Sunshine is not the only factor in their growth, he says. Oaks need a decent level of moisture, as well as the mycorrhizal (pronounced MI-cro-RI-zal) underground fungal networks that allow older trees to nurture and encourage growth in younger ones.

Fellow activist Sam Stearns also lives on the eastern side of Shawnee. He, too, has kept a close eye on the aftermath of logging. He says hardwood and pine stands logged prior to the 1996 stoppage have not fared well.

“Instead of the oaks and hickories, which the Forest Service promised would result from logging, it actually resulted in more beech, maple, and pines, so thick you cannot walk through them. This is the opposite of what the agency claimed would happen,” Stearns said.

Stearns and Wallace are also concerned about erosion that occurs after trees are removed. The muddying of Big Creek and other pristine water features at Shawnee have occurred, they say, because without trees and their deep root systems, nothing is left to keep the soil in place.

In Defense of Intervention

Tim Pohlman, district ranger at Shawnee National Forest, agrees that some of the older logging projects did not work out well in the long run for oak reproduction. He puts part of the blame on the fact that his agency wasn’t allowed to do thinning, controlled burning, and herbicide treatments for many years, so it was not able to create the environment the oaks would need.

Shawnee’s famed Garden of the Gods is protected from logging. (Terri Waters)

“Our guiding philosophy is to take actions necessary to maintain oak and hickory species,” Pohlman said. “As the canopy of the forest closes up, these trees can’t reproduce as well. Our timber sale practices are to encourage the opening up of the canopy.”

He defends the need for these interventions, including prescribed burns and spraying of herbicides to control invasive plant species. Pohlman also says they are going “a little lighter and slower” than in the past, leaving more trees standing.

Differing Points of View

Opponents of logging in Shawnee say the Forest Service is not interested in hearing what the public says.

“We have tried to talk to the Forest Service. We’ve done a lot of research, and we comment on the projects. They won’t address the science we present,” film producer Cade Bursell said. “Public dialogue is not something the Forest Service wants.”

Pohlman says that his agency does address the comments, but “a lot of times what happens is we have a different philosophy” about what needs to be achieved in the forest.

“We stay with the forest management plan, which is very oak-centered,” Pohlman said. “We provide the science that we’re using, but people either aren’t believing us or have a different opinion philosophically.

“We think the forest does a great job of sequestering carbon and also provides habitat for certain bird species and a variety of wildlife,” he continued. “To [achieve] that, we prescribe-burn and harvest trees. The Forest Service is an organization that cuts trees — it’s in our Congressional mandate. But it’s not carte blanche. A lot of environmental regulations are put on it.”

The larger trees that are vigorous should be left behind, Pohlman says, but observers like Stearns and Wallace say that’s not what they see.

Logging Projects in the Pipeline

The Forest Service is currently managing five different logging projects, some still in bidding stages, and totaling about 8,900 acres. Pohlman says these will occur over the course of many years and could average 1,000 acres per year. The agency also oversees several thousand acres of prescribed burning annually.

Shawnee Forest trees marked blue for logging.

He says the timber cutting overall has “a small effect on the carbon sink. It’s difficult to measure or quantify. Meanwhile, there’s the benefit to habitat, diversity of species [if more oak trees are growing]. There’s a whole equation to consider. To make a huge difference [for climate change], we probably need to look at areas that aren’t forests now. We look at it as a pretty good carbon sink now, with some pretty good climate benefits.”

Still, that’s not enough for Stearns and Wallace. The two have sued the Forest Service a couple of times, which gets expensive. Instead, they’re taking a different path: a campaign to convert Shawnee National Forest into a national park. This will take, literally, an act of Congress, moving the management of Shawnee from the U.S. Forest Service, which is under the US Department of Agriculture, to the Department of the Interior. It’s no easy feat, but the two remain optimistic.

Wallace wants to see the Shawnee established not only as a national park but also as the nation’s first “climate preserve” that allows for uses such as hunting, trapping, dispersed camping, and a few other activities that recreationists currently enjoy in the Shawnee National Forest but that are not permitted in national parks. Parks deal only with preservation and recreation, but the Forest Service manages mining, oil and gas drilling, and logging.

“We need to protect the best mechanism we have for capturing carbon — our forests. We need them for carbon sequestration and carbon storage. Public land is the best way to do it,” Wallace said. “We have very few national parks in this area. We need more.”

Learn More About Logging in Shawnee National Forest

Watch the Film Trailer – Get a sneak peek at Shawnee Showdown: Keep the Forest Standing at vimeo.com/619337732.

Free Guided Tours – Visit areas of Shawnee that have been logged in the past, and areas that are slated for logging soon. Contact Sam Stearns at bellsmithsprings@hotmail.com.

Shawnee Forest Defense – Stay up to date on the fight to protect Shawnee and sign a petition to stop future logging at shawneeforestdefense.info.

Shawnee National Forest Headquarters – For general information about Shawnee National Forest, call 618-253-7114 or visit fs.usda.gov/shawnee.

Author: Terri Waters is a regular contributor to Terrain Magazine.

Top Image: A muddy, clear-cut area of Shawnee National Forest.

To put things in context, even if the Forest Service cut 8900 acres of trees, that is only .033 percent of the Shawnee National Forest. Also the Shawnee Forest Defense are touting increased tourism as a reason to support their National Park proposal. Increased tourism is in direct conflict with what the Shawnee Forest Defense define as the propose of a Climate Preserve. While the Defense group stated they are not being heard by the Forest Service, they themselves are not listening to all the other users of the Shawnee National Forest who love the Shawnee just as much as they do and oppose their proposal. The Shawnee Forest Defence state they welcome conversions. But we who have tried to engage them in those conversations have experienced just the opposite. They also discount science based facts that contradict with their version of reality. To quote a friend, they want no conversation, only converts. There’s much more I could write in opposition of the proposal but the real truth is that no matter what the Shawnee Forest Defense proposes, and while there would be public input, it would be the National Park Service who would decide the fate of the Shawnee National Forest. The Shawnee National Forest could be eliminated for what, no one knows. It could change everything that makes the Shawnee National Forest the amazing place it is.

PS- My thanks to the author for contacting and speaking with the Tim Pohlman, district ranger at Shawnee National Forest, The Forest Service employees working in the Shawnee National Forest are wonderful, dedicated people who care for the Shawnee National Forest as much, if not more, than anyone.

Sam and John are back to their old tricks! They couldn’t care less about a National Park designation . It goes against their prior beliefs of keeping people OUT of the SNF! They are merely using that construct as coattails to ride in on! More people? More businesses? More infrastructure? That’s not the Sam and John I know!