Before 2021, the Ozark Trail Association (OTA) would receive about $15,000 annually from the federal government to maintain 364 miles of trail in the Mark Twain National Forest.

“That’s not a whole lot of money, considering our insurance runs about $11,000 a year just to get boots on the ground,” said Kathie Brennan, OTA president.

Then, the nonprofit organization received a $50,000 federal grant as part of the Great American Outdoors Act, a bipartisan bill to maintain National Parks and other outdoor areas. The government later increased the grant to $150,000.

That money has allowed the OTA to hire seasonal workers to maintain parts of the trail.

Despite that recent progress, and a continued nationwide emphasis on increasing outdoor recreation opportunities, the association still has about 270 miles of trail to develop, according to Brennan.

The groups behind two other Missouri trails — the Brickline Greenway and the Rock Island Trail — have also moved closer to their goals in recent years, but project supporters say they still face challenges related to funding, regulations, and community support.

“I’m excited to see what’s possible in terms of having [the Brickline Greenway in St. Louis] be a catalyst for job creation and filling in some of our vacant parcels, helping to strengthen neighborhoods and build pride with all these different communities we’re connecting,” said Emma Klues, vice president of communications and outreach for Great Rivers Greenway, the public agency overseeing the effort. “These projects are so complex that it’s really more lots of little challenges.”

Here’s a look at where the Ozark Trail, Brickline Greenway, and Rock Island Trail projects currently stand, their scopes and visions, and what hurdles they face to achieve their goals.

The Ozark Trail

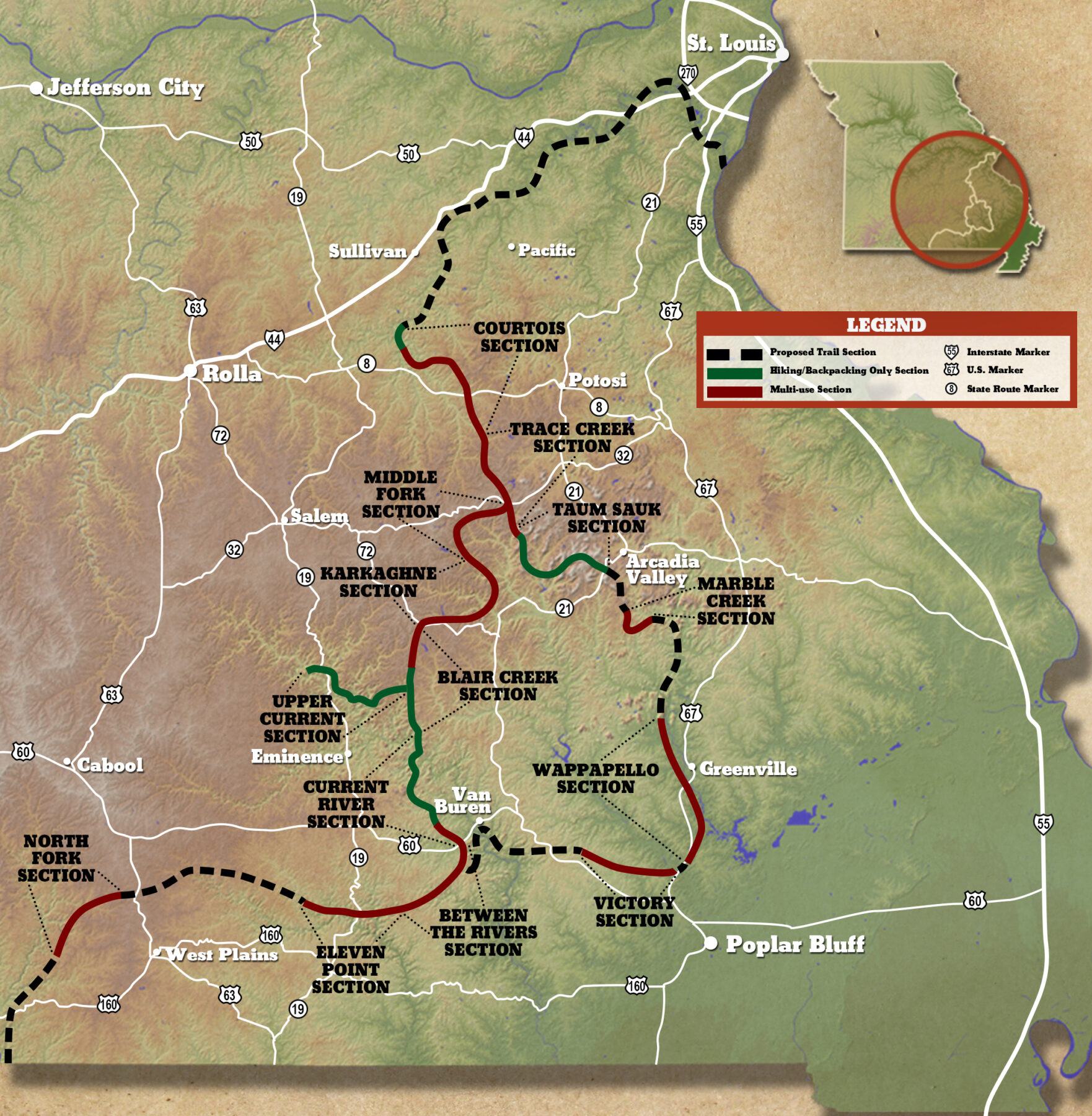

The result of an idea conceived in 1977 to run a trail from St. Louis to the Arkansas border and eventually connect with the Ozark Highlands Trail in Arkansas, which would create a 700-mile thru-trail. All completed sections of the trail are open for hiking, with some sections also open for bicycle and equestrian use.

These days, the Ozark Trail (OT) consists of nearly 400 miles of natural-surface footpath that winds through the rugged and beautiful Missouri Ozarks. But the 14 named sections — which range in length from about 10 to 50 miles each — remain separated.

Connecting them will require hundreds of thousands of dollars and countless volunteer hours, says the OTA’s Brennan.

The vision is for the long-distance hiking route to become a household name, like the Appalachian and Pacific Crest trails, and drive outdoor recreation tourism and economy in central and southern Missouri. To make that happen, volunteers must restore parts of the trail that have not been touched for 50 years, says Brennan, and this takes money and manpower.

OTA volunteers not only work to obtain funding but also “adopt” parts of the trail that they agree to maintain. This can require three or more maintenance trips each year, which the volunteers must fit in amidst their often busy professional and personal lives.

In one case, a funeral director and volunteer had been talking with county commissioners in southern Missouri about connecting a 25-mile gap between sections of the trail when the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020. The volunteer’s life suddenly became much busier, and “everything just kind of shut down,” Brennan said.

But as society has reopened, volunteers have returned to the OT. In mid-March, Brennan and three others spent four days on the trail near the Eleven Point and Current rivers. Storms during the winter knocked down branches and whole trees that blocked parts of the path. Brennan and another volunteer spent four hours clearing just one mile of trail.

“That’s the intensity of [maintaining] some of the sections,” Brennan said.

Other challenges exist. State and federal land managers must still negotiate with private landowners to obtain easements for parts of the trail.

All-terrain vehicles became much more popular during the pandemic, says Brennan, which meant a spike in illegal use of the machines on the OT. “Sometimes it’s not even worth going in and trying to reestablish the [original] trail,” she said.

But the OTA has been able to make progress in recent years, in part because federal funding allowed them to hire a seasonal National Park Service ranger and an AmeriCorps alum to help organize volunteer efforts.

In addition to clearing vegetation from the trail, the organization has worked on tread restoration, repairing kiosks, and constructing new ones.

“People that are using the trail are seeing the improvements,” said Brennan. “It’s not just little stuff, but it’s the bigger picture of trying to take care of a trail that’s been around for decades.”

In 2021, the association spent more than $130,000 on the construction and maintenance of trail, promotion, administration, and other expenses, according to its annual report. More than 800 people volunteered for a total of 9,581 hours.

Brennan and other volunteers remain optimistic, even though it could take years to close the gaps in the trail.

“We’re adding footage to the trail,” she said. “But with it being a very grassroots volunteer organization, it’s just taking time.”

The Brickline Greeneway

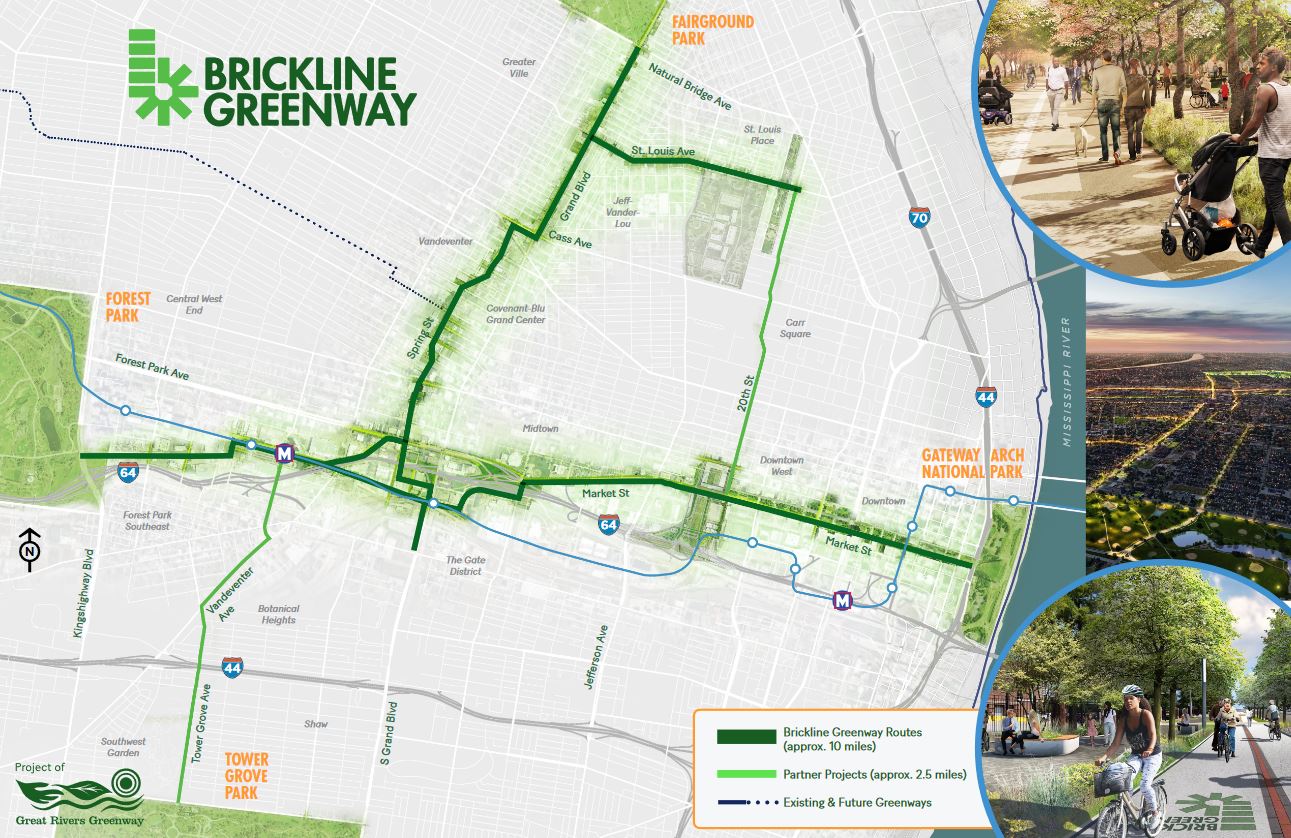

This urban greenway is a 10-mile paved path intended to connect St. Louisans to their schools, workplaces, neighborhoods, and civic and cultural institutions. It is part of a growing 128-mile network of greenways in the three-county region that is being developed and maintained by Great Rivers Greenway.

In June 2022, the Biden administration announced it would invest $1 billion in infrastructure to reconnect communities that were cut off from economic opportunities by transportation infrastructure designed to benefit people outside of such urban areas.

“It could mean constructing a public greenway that allows people to walk, bike, and access public transit, [like] in St. Louis,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said at the time.

He was referring to paths like the Brickline Greenway, an ongoing project that would feature a network of 10 miles of walking and biking paths in the City of St. Louis. The idea is to connect Forest Park to Gateway Arch National Park and Fairground Park to Tower Grove Park, with a loop in the middle.

The group behind the project, Great Rivers Greenway, was established by leaders in St. Louis city and county and St. Charles County in 2000 and has received more than $42 millions of dollars in local, state, and federal funding. With private funding, it has obtained about $75 million of the estimated $245 million cost for the Brickline project.

A report commissioned by Greater St. Louis, Inc. found that the Brickline would drive hundreds of millions of dollars in economic growth in the St. Louis metro, an impact that “far exceeds the initial investment.” Development of the greenway will also “result in numerous other social and economic benefits — including environmental, health, and safety improvements — for the region.”

But the leaders of Great Rivers Greenway say they still face a big challenge in ensuring that people who live along the path benefit from its construction. Residents in the often predominantly-Black communities had no say in the construction of highways and other infrastructure decades ago, which then disrupted their lives, according to experts.

“We want to make sure we’re working directly with the people who live and work in these areas now, to make sure that it can really create shared prosperity for everyone,” said Klues.

Even today, such projects can have unintended consequences. The so-called “green space paradox” refers to the fact that such infrastructure can draw additional investment into the neighborhoods and increase property taxes and rent beyond what residents can afford.

To avoid that, Great Rivers Greenway staff want to secure affordable housing options near the path and possibly tax credit for residents, Klues says. The organization also regularly holds public meetings, block parties and trash pickups, and conducts surveys in neighborhoods along proposed routes to get input from residents.

“It’s really a whole mix of tactics to try to make sure that we’re meeting people where they are and connecting with them through the places they already meet and gather,” Klues said.

The first actual bricks of the Brickline Greenway were laid on Market Street this past January, and in late February, Great Rivers Greenway and its partners, including the City of St. Louis and the St. Louis City SC soccer team, opened the Pillars of the Valley plaza on the Brickline at CITYPARK stadium. The monument commemorates the once-thriving Mill Creek Valley neighborhood that was destroyed in 1959 and its 20,000 Black residents displaced in the name of “urban renewal.”

“So far, we’ve had very solid community buy-in and feedback,” said Klues.

That support will be crucial as the organization tries to complete the remaining five miles of the Brickline. The architecture and engineering firms SmithGroup and the Lamar Johnson Collaborative are designing parts of the path along Market Street, the MetroLink line between the Cortex and Grand stations, and from Fairground Park to the Grand station.

The group already has funded much of those segments and hopes to begin constructing them in 2025. It hopes to have the entire greenway finished within the next decade.

In the meantime, Klues is among those who use part of the Brickline when biking to work. She rides on one block of greenway during her commute from the Shaw neighborhood to her office in St. Louis City Foundry.

“It sounds silly to think of a block making a big difference, but it’s something to be able to even just let people continue to familiarize themselves with what a greenway looks like,” Klues said. “It’s lovely to be a little bit separated from traffic and have that break where there are native plants along the way, and I do breathe a little differently when I’m on that section versus on one of the streets.”

The Rock Island Trail

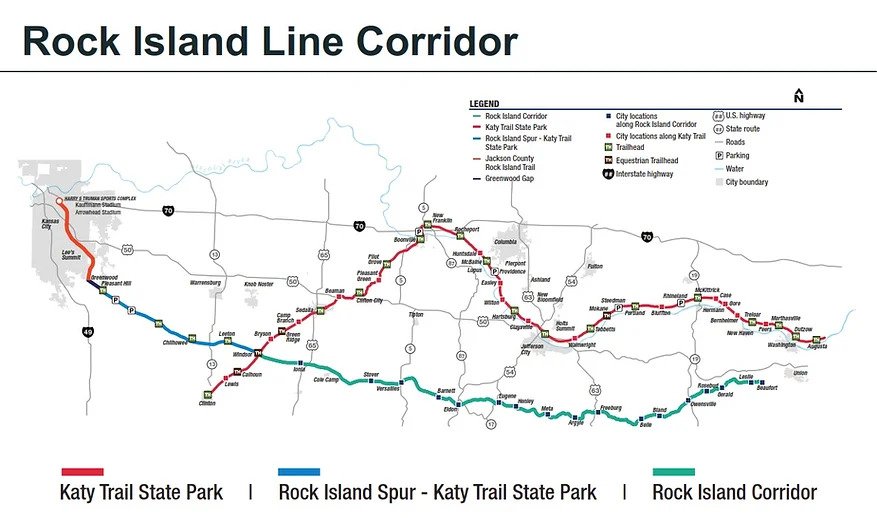

An effort to develop the 144 miles of the former Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad corridor, which stretches from Windsor to Beaufort, Missouri, into a public recreational trail. Development would occur in sections over several years, as each section of the corridor has different features and challenges.

The Rock Island Railroad Corridor arrived safely in the hands of Missouri state agencies in late 2021. Unfortunately, since then, proponents of converting the former rail line into a biking and walking trail have not been able to secure state funding.

More than a year ago, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources (DNR) announced that it had received a $2.7 million federal grant for the project, which allowed the state to take ownership of the corridor from utility company Ameren Missouri.

Governor Mike Parson pledged to spend $69 million in federal COVID relief funding to make the trail a state park. The Missouri House of Representatives approved the allocation, but the measure failed in the Senate.

Rick Mihalevich, president of Friends of Missouri Rock Island, says what bothers him about some state lawmakers’ resistance to the spending is that it is not even state money.

Another challenge is that some landowners along the proposed trail also have opposed the project, saying it would encourage trespassing and violate their property rights.

State Senator Lincoln Hough, a Republican from Springfield who chairs the Appropriations Committee, told the Columbia Missourian newspaper that the state should fund maintenance of existing state parks rather than the new trail, which he described as a “property grab.”

In September, a federal judge ruled that 150 Missouri landowners should receive federal compensation for property seized for the Rock Island Trail. An attorney representing the landowners told the Springfield News-Leader newspaper that the ruling would not interfere with state spending.

The Missouri Farm Bureau has also expressed opposition to the development.

Still, Mihalevich remains confident the project will take off because people in communities along the trail will see it as an economic opportunity and then lobby state lawmakers.

According to a 2011 study by Missouri State Parks, the Katy Trail, a similar rail-to-trail conversion, is used by about 400,000 people and brings $18.5 million in economic impact to the state annually. (That’s $29,153,418 adjusted for 2022 dollars and ridership.)

“[The Rock Island Trail] will have the support of the local communities once they see what kind of tourism it brings and the rural economic development,” Mihalevich said.

The remainder of the project will cost about $106 million, according to the Missouri DNR.

While Parson’s proposed $69 million allocation has evaporated, Mihalevich appears to have already moved on from that goal.

“The organic manner of these communities that are getting behind the trail is way more powerful than the handful of the general assembly members” who are opposed to the project, he said.

Author: Eric Berger is a regular contributor to Terrain Magazine.

Leave A Comment