Climbing is not an age-out sport. Right here in St. Louis, there’s a vibrant community of climbers in their golden years. Climbers like Chuck McGibbon and his wife, Becky Treiman, who started serious rock climbing in their 60s.

Sure, McGibbon had already bagged his fair share of fourteeners stateside before tackling Aconcagua in Argentina, Ama Dablam in Nepal, and Cho Oyu in Tibet (all over 22,000 feet). And yes, he kicked off his retirement by training for and reaching Mount Everest’s south summit.

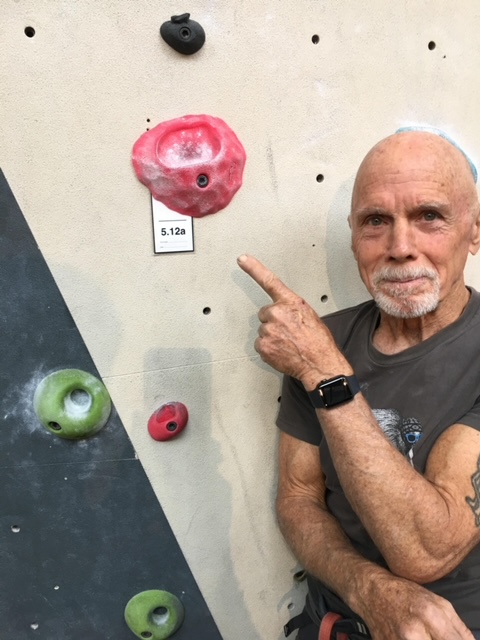

You might say McGibbon is a force — a force who is now an avid rock climber. The kind of force who spends more days climbing every week than not, who climbed more than 70 routes to celebrate his birthday of the same number, and who has set more than 50 sport routes at Robinson Bluff in less than two years.

McGibbon’s McEvolution

This force, however, did not get his first climbing gym membership until the age of 60.

“I remember wanting to learn how to lead climb. The lady behind the counter at the climbing gym told me, ‘You really should be able to climb 5.9s before you learn to lead.’ I wailed, ‘I’ll never be able to do that!’”

He was wrong. Those 70 routes he climbed for his 70th birthday, they were all 5.11s.

McGibbon’s indoor accomplishment.

“I was inspired by Jack Lalanne [the godfather of modern fitness]. When he turned 70, he towed a flotilla of 70 rowboats across Long Beach Harbor,” said McGibbon. “I wanted to do something in my 70th year, too. It seemed like a reasonable goal to red point at least 70 difficult, for me, routes in my 70th year. And I did it. I got 84.”

Several years after his platinum birthday, McGibbon tried his hand at route setting. Not at the local gym or even a Missouri crag — in Australia’s least populated and only island state, Tasmania.

“There’s good climbing in Tassie,” said McGibbon. “Where else can you climb on sea walls and watch giant whales go by on their way to Antarctica?”

When McGibbon and Treiman were there in 2017, a new climbing area had recently been discovered, a sequence of sandstone cliffs called Sand River. That’s where he started setting.

Bring It on Home

After his bolt-setting initiation in the Land Down Under, McGibbon returned to St. Louis with a handy new skillset. Then…COVID.

“I was climbing with Bill Weishaar [owner of Robinson Bluff in Tiff, Missouri],” said McGibbon. “Bill asked if I was interested in setting routes at Robinson Bluff. It seemed like the perfect opportunity to keep socially distanced while still being active during the pandemic.”

So, McGibbon started developing Robinson Bluff, and he never stopped. He’s made more than 250 trips and contributed nearly 30 percent of the destination’s sport routes. But that’s not all. McGibbon spends days — literally days — cleaning routes he didn’t set, retrofitting anchors with mussy hooks, building and clearing trails, hand-crafting name plates for routes, and all around making the property better for climbers.

How Routes Are Set

Route setting is an art form for a rare bunch. It starts with finding a rock face that looks challenging but not impossible. Then, cleaning the rock. And finally, placing the anchors and bolts. Sounds quick and easy. It’s not.

McGibbon installs a name plate at Robins Bluff. (Jon Richard)

“Sometimes, there’s a lot of brush to remove,” said McGibbon. “Sometimes it’s easy [think pebbles, dirt, leaves, moss, vines], but other times it might be an entire tree. That’s the first step, getting to the rock.”

Then, he trades his chainsaw for a hammer, crowbar, and chisels. He begins banging on the rock, interpreting the sounds and vibrations. He looks for weaknesses like fractures, loose flakes, and cavities. All of this while dangling 20, 60, or 90 feet above the ground for hours.

“Then, I figure out how I’d climb it and where the anchors should go. I try it on top rope or by jugging up a fixed line a few times [he always sets on rappel], looking for decent rock to place the bolts. Then, I start drilling and gluing.”

McGibbon says it takes him at least three, eight-hour days to set a single-pitch route. That’s a significant time commitment for volunteer route setters who usually end up paying for their own tools and hardware, too. (Note: Thank route setters, thank them often.)

“Bill has been so supportive,” McGibbon said. “He supplies most of the tools, bolts, chains, quick-links, mussy hooks, and epoxy. These things are not cheap. The average route usually has at least $100 of hardware invested in it.”

A Look Ahead

As Robinson Bluff inches toward its route capacity, McGibbon and other developers are looking at individual lines rather than entire walls. A mountain bike trail now meanders the property. The number of campsites has expanded in the last six months, too, and there’s a brand-new bathroom with shower on site.

As for McGibbon, his next aspiration is no less extravagant than any preceding it.

“My goal is to red point at least 1,000 routes of grade at least 5.11a by the time I reach 80. I’m up to 842 now and am almost 78. I’ve got my work cut out to reach that goal.”

Author: Corrie Hendrix Gambill is a regular contributor to Terrain Magazine.

Top Image: McGibbon climbing at Robinson Bluff. (Jon Richard)

Leave A Comment