Time magazine “Hero for the Planet”. A leading botanist and conservation and biodiversity advocate. Winner of the US National Medal of Science. Four-decade president of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Dr. Peter H. Raven’s list of credentials and accolades feels nearly endless.

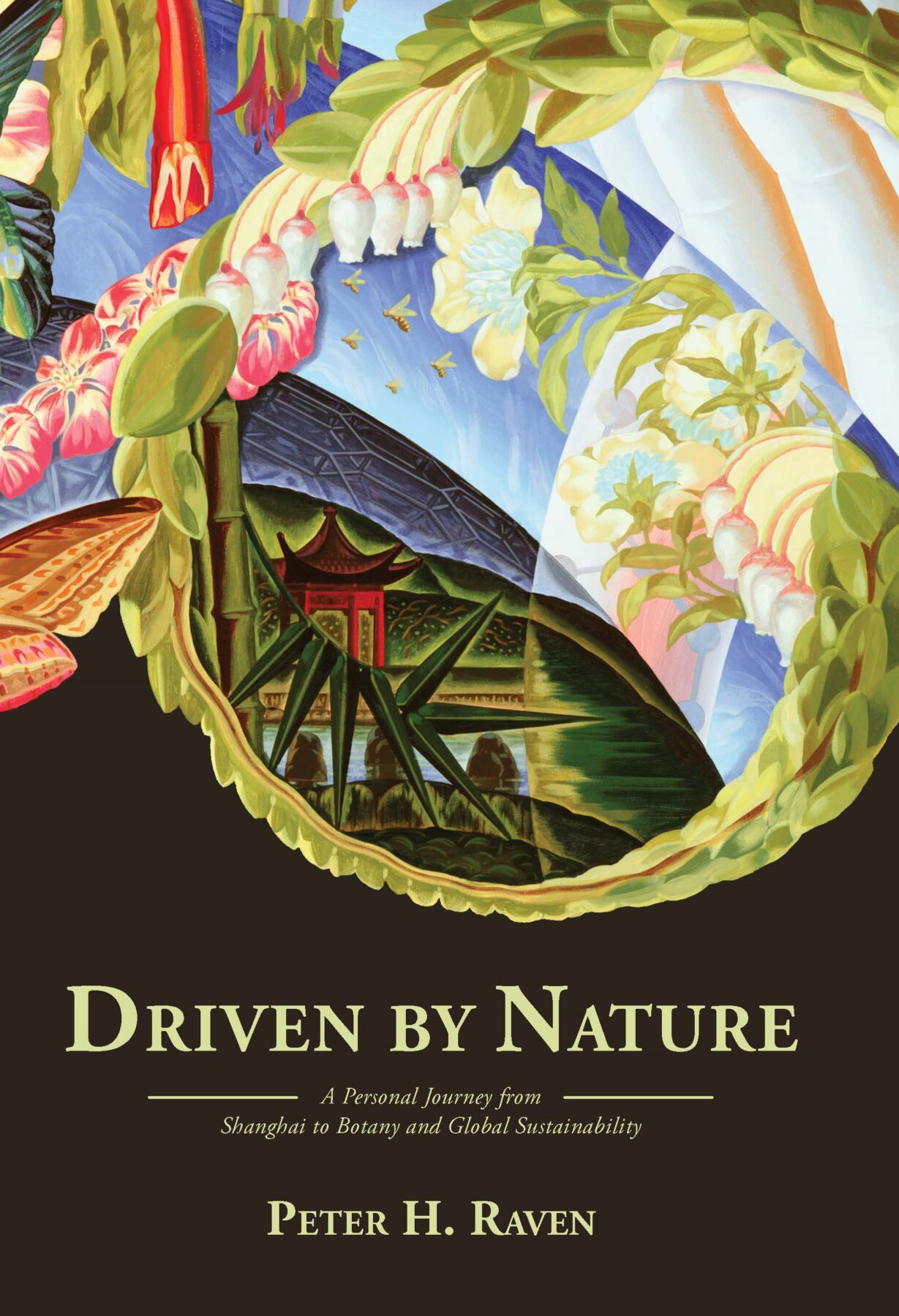

Arguably the most important nature champion to call St. Louis home, Dr. Raven recently published Driven By Nature: A Personal Journey From Shanghai to Botany to Global Sustainability. The book describes Dr. Raven’s life, from his birth in Shanghai in the 1930s, his family’s subsequent move to San Francisco, where his love for nature began, and his long career dedicated to plants and the environment.

Terrain chatted with Dr. Raven about his book, his impact on St. Louis, and his advice for making a positive impact on the environment today. Our conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.

What inspired you to write your memoir?

I’ve lived at a particularly interesting time in the history of the world. I wanted to share how our understanding of the world has unfolded during the years I’ve been alive. I was born in 1936, and the first evidence that climate change was being caused by atmospheric gasses came in the 1950s — it took us a long time to pay attention. Then, in the late 1960s, people began to see that all kinds of plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms were disappearing.

I came to the Missouri Botanical Garden in 1971 from a faculty position at Stanford University and was soon met with the challenges facing the world at the time — the way it played out in my life and the garden is the story I tried to tell in the book. I also wanted to inspire young people to get into biology like I did. A third theme is the garden and how it evolved and grew during my time as president.

Your leadership made the Missouri Botanical Garden what it is today. Tell me about your work there.

Like other key cultural institutions in St. Louis, our garden is deeply loved by many people. What was needed was to bring the garden more into the public view. Only about one-third of the present area was cultivated when I began as president. We did a lot to turn the garden into a lively, interesting, evolving, and dynamic place. Now, we have about 50,000 members and get a million visitors each year, compared to around 2,000 members and fewer than 200,000 annual visitors in the early 1970s.

You also transformed the garden into a world-class center for botanical research — it now employs research all over the world. Why was this important to you?

In the 1920s and 1930s, the garden was one of the most important places in the US providing training in plant evolution and identification and so forth. It already had one of the best plant libraries in the world — when I arrived, we had about 2 million dried plant specimens for study in the herbarium. So, the garden was already a substantial institution, semidormant at that time, just beginning to awaken. Everything we did from then on was to expand upon those things, making them better and more worthwhile to understanding the plants of the world in an era when they’re being threatened with extinction.

Why are gardens important?

Plants and gardens beautify our lives in ways that have been an inspiration for the entire history of humanity. Now, gardens also demonstrate conservation and sustainability, in respect to energy use, conservation, and preventing plants and animals from becoming extinct. Gardens are one of the forefront organizations enabling people to appreciate the world we live in and wanting to save it.

Your book also touches on the environmental crisis we’re facing. Do you have any advice to share for readers who want to take action?

If everybody in the world consumed as much as we do in the US, it would take four planet Earths to sustainably support us. That’s why it’s important that we realize the impact a wealthy country like the US can have and stimulate our own government to care about the rest of the world. It’s important to teach our children about the environment and promote an international understanding.

Empowering women worldwide is also extremely important — we have come a long way to put women on an equal standing in the US, but worldwide the situation is far more serious and tends to lead to mindless growth without the intellectual contributions of hundreds of millions of women throughout the world.

And then, of course, living sustainably in our own households.

Do you feel hopeful about the future?

The future’s going to be rough, but what we do about it now is going to make a big difference. We can choose to sit on our seats and let it happen, or we can choose to take action. I strongly recommend the latter.

What are you working on now?

An important thing for me is to continue to encourage others. One way I do that is by connecting people with one another. I keep up a ferocious pace of email correspondence to keep encouraging people, to help them see that what they’re doing is important.

Author: Stephanie Zeilenga is a regular contributor to Terrain Magazine.

Leave A Comment