The messages started coming fast and furious. There were texts. Facebook instant messages. Emails from my bike group, co-workers, and others who knew I was a cyclist.

“Did you see this? Some guy has ridden his bike on every single street in St. Louis!”

The links went to a post on the Humans of St. Louis Facebook page. A South City cyclist named Paul Fehler was featured for this amazing accomplishment. I wanted to find out more.

“If this city ever starts to feel small to you, just try to bike down every street,” Fehler wrote on the page. “Somebody showed me a post by a guy who did that down every block of Manhattan. I finished the same thing in the City of St. Louis…. It ended up being 1,800 miles of streets and 18,000 bike miles. It took me about three-and-a-half years of daily grinding: 1,304 rides and over 914 days.”

The Humans of St. Louis post brought a lot of attention to Fehler for this remarkable achievement. It also surfaced a handful of other cyclists who had completed the same feat.

“I always say that if it had been just me who did it, well, that just sounds like mental illness. But once two people had done it, then it was an ‘interesting quirk.’ And now that three people have done it, it might even rank as a ‘small trend,’” wrote Fehler.

He named two others, Richard Egan and Wayne Burkett, who had similarly, working block-by-block, conquered the entire City of St. Louis by bike.

There were many things that were very intriguing about this to me. The adventure. The challenge. The pointlessness of it all.

“Why did you climb Mt. Everest?” someone asked British mountaineer George Mallory, who took part in the first three British expeditions there in the early 1920s.

“Because it’s there,” he replied.

Why would someone take on a crazy challenge to ride every street in a particular city? Well, because it’s there. It’s this sentiment that motivates a small cadre of bicyclists in St. Louis. They are driven by an outsized sense of adventure and an almost obsessive focus to systematically ride every block of every street — including the endless dead ends and cul-de-sacs normally shunned by cyclists — until they’ve checked off every last possible mile.

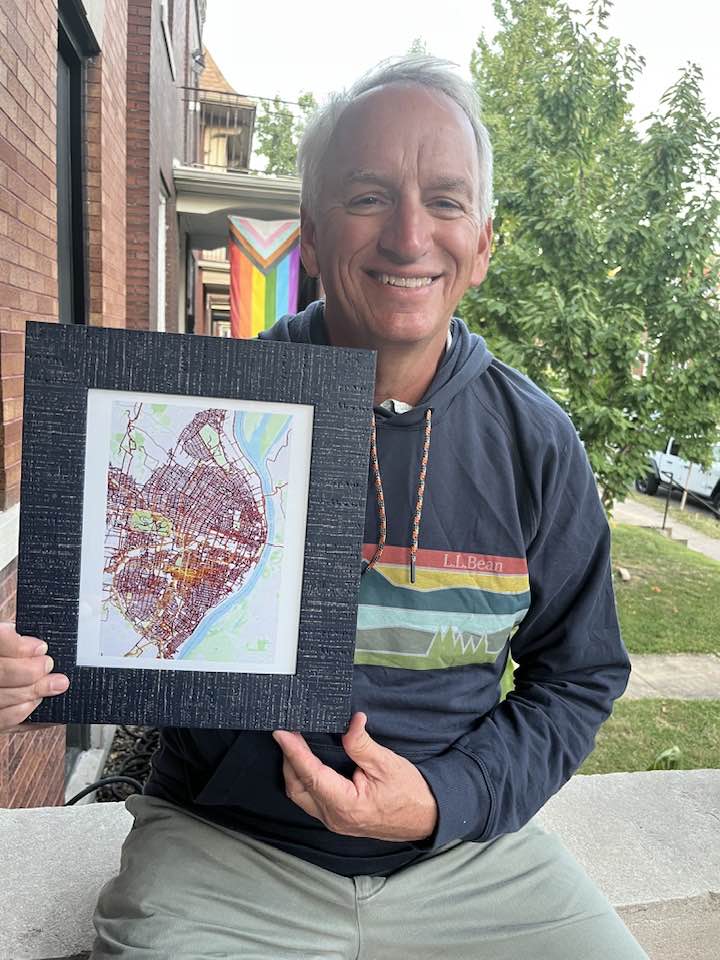

Richard Egan: Cartography Crazy

Richard Egan is passionate about many things: cycling, maps, and music among them. When he retired as a cartographer for the US government, suddenly he had a lot more time to pursue these passions. He plays in the Mound City Slickers, an old-time string band, to get his music fix. His other two interests, maps and bikes, got combined in a gradually developing quest to ride every street in the City of St. Louis.

“I’m not a road biker,” said Egan, who logged around 4,000 miles a year as a bike commuter, riding year-round from his home in Tower Grove South to the Defense Mapping Agency near the Anheuser-Busch brewery south of Soulard. “I’ve been out there for the last 15 years on a city hybrid bike set up to handle the potholes and broken glass. It’s a great way to keep your blood pressure down and certainly a great way to see the world.”

But riding every street in the city was a completely different challenge than his 3-mile daily commute. What caused Egan to take this on?

“When I looked at my Strava heatmap, I realized there were a lot of streets right in my neighborhood that I’d never been down. Dead-end streets. Ones in more marginal neighborhoods nearby where people were living but that I’d never seen before,” he said. “I just wanted to say that I’d ridden them all.”

Egan didn’t set out to conquer the whole city at first, just his immediate neighborhood. But once that was done, it was natural to continue the quest. After Tower Grove South, he next rode the entirety of the adjacent Bevo neighborhood, then just rolled on from there.

“It was a little bit haphazard at first,” said Egan. “Some days, I’d feel like going west, and I’d be in the Hill or North Hampton or wherever. Then, I started heading south, depending on what I felt like. By the end of 2020, I’d finished most of south and central St. Louis.”

Egan faced a bit of a dilemma once the “easy” neighborhoods closer to home were complete. The quest to ride the entirety of the city still had not been formalized in his mind, and the areas that remained were getting farther away and less familiar.

“I stopped for a couple months and rode all the streets in Webster and U City,” he said, candidly. “I questioned my courage. I thought I was evading things I was afraid of.”

Egan reckoned that the best way to resolve this was to just keep taking little bites at the bigger task, to simply keep riding, slowly knocking out the city block by block.

“I decided to systematically continue, just one neighborhood at a time, and see how it went,” he said. “It wasn’t until I got right to the end that I suddenly realized I only had a couple neighborhoods left until I’d have finished the entire city.”

Egan completed his quest on Memorial Day weekend in 2022, having logged some 1,800 miles in the process. His sweetheart was there to video him riding the very last block.

What struck him about St. Louis as a result of this experience?

“The city is much larger than you imagine when you’re just driving through the neighborhoods,” he said. “The population was 850,000 in St. Louis in 1950, and even though there are only 300,000 now, the infrastructure is still there to hold that many people. You certainly realize it when you’re out on the bike.”

When asked what he learned about himself, Egan paused reflectively for a moment.

“Perseverance,” he said. “I learned that perseverance is the key. What seems impractical or even impossible can be done over time. I’m not a great athlete or cyclist, but I did it little by little, just out rolling along and having some fun.”

Mike Bockserman: The Wandrer

“I’m not the fastest rider, and I don’t have the most miles or the most consecutive days riding, but I’ve seen more of the St. Louis area on a bike than anyone else, and I have the metrics to back it up,” said Mike Bockserman, who lives in Creve Coeur and works as an engineer for Boeing.

He got started in his version of this endeavor when he paired up with his daughter, Katie, a former bike racer, to help her snag as many Strava QOMs as possible. (Strava is a popular fitness app, particularly for runners and cyclists; in Strava-speak, QOM or KOM is shorthand for Queen/King of the Mountain, which designates the person who holds the fastest time for any given segment.)

They began visiting out-of-the-way places to pursue QOMs on segments that only a few people had ridden. At her peak in 2014, Katie owned an astonishing 500+ QOMs. It was a great accomplishment for her, but it opened her dad’s eyes as well.

“I realized that riding with Katie in all these different places, I suddenly had a very cool looking Strava heat map at the end of the year showing where I had been,” he said.

Things went to a whole new level for Bockserman when he fired up Wandrer, a more recent app that not only tracks all the streets where a person has walked, run, or ridden, but also maintains leaderboard rankings based on points a participant has earned based on the percentage of road miles they’ve covered in a defined area.

“It’s kind of addicting,” Bockserman said. “You’re always looking for new streets to ride.”

Wandrer has a twist, though, in that bonus points are awarded for completing high percentages of miles ridden in a specific municipality. With that new insight, Bockserman knew he was onto something. There are more than 90 unique cities in St. Louis County, which meant there was a massive pile of points to be achieved right outside his front door. His challenge shifted. It was more than just knocking out miles but also being strategic on earning points in order to work his way up the Wandrer leaderboard.

How does this work in real life? Take Bel-Ridge, Missouri, for example, a tiny North County municipality that doesn’t even cover one square mile. After Bockserman rode the community’s relatively few streets, Wandrer tallied the actual distance ridden and then applied the magic multiplier for completing another municipality.

By checking off so many of these small St. Louis County communities — Bel-Ridge is just one of eight different cities a person can pass through in a short stretch of Natural Bridge Road near UMSL — Bockserman towered atop the Wandrer rankings, even compared to people who might have ridden more total miles in St. Louis County or even statewide.

“Nobody’s ever going to catch me in Missouri,” he said. “I’ve got St. Charles County and St. Louis County locked up, too.”

The numbers back it up. Bockserman is at least two times higher in the Wandrer scoring system than his nearest competitor in each of those geographies.

Bockserman’s quest to ride as many unique street miles as possible has meant he has covered a good portion of St. Louis Count — more than 80 percent of its 5,900 road miles and counting. He is now starting to work the more far-flung portions of the St. Louis metro area, as well as to chip away at the City of St. Louis itself.

It remains a departure from the typical weekend group ride.

“It’s a different style of riding,” said Bockserman, “usually quite a bit slower due to constant turning. Over the last few years, I’ve spent more hours on the bike but actually rode fewer miles. And I go through more brake pads than most people, since I’m constantly slowing to turn or riding around a cul-de-sac.

“Typically,” he said, “I can’t get my friends to ride this way with me.”

Benton Boice: Car-Free Living

“Riding over 99 percent of St. Louis is one of the achievements I’m most proud of,” said Benton Boice, who moved to St. Louis from Kansas City in December 2021. “Nobody told me I had to do this. It was something I did on my own.”

Boice, who lives with his wife in the city’s North Hampton neighborhood, is an advocate of car-free living and rides everywhere, including to his job at the Trek Bicycle store in West County. While he says he enjoyed exploring the city, his rides were often loosely planned and, at first, he would go out and just let his wheels take him wherever.

“St. Louis is such a bike-friendly place,” he said, “I was always out exploring new areas and seeing new things.”

Boice had already been tracking his rides on Strava after moving here, but his quest to cover all of St. Louis City became a lot more intentional when Boice joined Wandrer, which pulls historic data for past rides from Strava. Even as a new user, he saw that he had 30 percent of the city already covered just from living his daily life on a bike.

“I do a lot of meandering riding,” said Boice, “and that’s what I love about having this focus. Now, there’s a real incentive to identify those streets that I haven’t done before and make a point to cover them.”

For a guy who knocked out the entire city proper in such short order, Boice is surprisingly nonchalant about what he plans to tackle next on his bike.

“I’m bad at goals,” he said. “More than worrying about Wandrer, my goal is to have fun riding my bike. Sometimes that’s new miles, sometimes it’s a meandering commute, sometimes I’m just replacing a car trip with my bike.

“I’ve got a bike trip to Amsterdam planned for May,” Boice continued, “and crossing a country border by bike is something I’m stoked to accomplish. Otherwise, my current goal is to accomplish at least 25 percent of every St. Louis County municipality. I don’t really have a timeline, but I figure I have to complete it by the time my current rental agreement is up in July 2024.”

Practical Tips: Riding Every Street

Our cyclists have tips to share for people who want to take on a similar quest of riding every street in their neighborhood, their municipality, or some larger portion of the region.

“Regardless of the geography you’re trying to cover, start by breaking it down into smaller areas,” suggested Egan. “Go street by street, neighborhood by neighborhood, not the entire city or region at once. It’ll give you a great sense of accomplishment as you see your steady progress. It was always fun for me to see the Strava heatmap fill up just a little bit more each time I was at home after a ride.”

There are lots of great apps out there such as Strava or Wandrer that will track your rides, so take some time to figure out what works best for you in capturing your efforts. Could be digital, or perhaps not. Egan spent his career working as a cartographer, and along with Strava, he used good old-fashioned paper maps and a grease pencil to track his progress.

“[St. Louis] City has 79 distinct neighborhoods, and it offers great maps of each one on its website,” he said. “I printed them out and used them to plan and document my rides.”

Using GPS technology. The riders we talked with were fanatical about making sure that they covered ALL the streets in a given area. They didn’t want to get “most” of them, and to have any sort of gap on the map was the type of thing to drive these folks crazy.

If you are using GPS technology, our featured cyclists learned some tricks to make sure that it truly captures what has been ridden.

Bockserman noted that Strava GPS pings every 10 seconds, and Rob Anderson, a cyclist from Webster who has currently ridden about 60 percent of the City of St. Louis — plus nearly all of Shrewsbury, Crestwood, and Webster Groves — pointed out that civilian GPS is only accurate within about 10 feet on a good day. This reality can lead to those maddening gaps on a coverage map, where it falsely shows places a cyclist has not yet ridden. Intersections are problematic, says Anderson. Cul-de-sacs too.

“Sometimes, it takes three tries to cover an area like an intersection to get it to register correctly,” he said.

As a rule, Bockserman rides each cul-de-sac twice to ensure the GPS has read it properly; once close to the inside of the court and a second time up against the outer edge.

Be Prepared. This sounds like the normal caveat about carrying a patch kit, tools, etc., but urban adventurer Boice reminds us that this style of riding is truly different. Make sure that you have things like sufficient nutrition, charged lights, and an extra battery for your phone when you are headed out to explore unfamiliar and/or neglected parts of town.

“It’s not the same level of complexity as unsupported touring, but you need to be pretty self-sufficient,” he said. “It’s easy for 30 miles to turn into 50 and then into 100 when you’re out having fun. You want to be prepared.”

What defines a street? Seems easy to answer, but in reality, this is a serious question with some nuance. Interstates are not part of this quest, since bikes are not allowed on them in the St. Louis area. Alleys are not generally part of the challenge either. Golf courses and their cart paths also do not count, nor do footpaths in parks. You can decide for yourself about how you want to handle private streets or roads that run through graveyards and parks, but our riders generally agree that if a street shows on a map and is accessible to the public, they want to ride it.

Also, you’ll certainly experience situations where roads that show up on a map do not exist in real life. They may be fenced-off inside an industrial facility, for example. This is frequently the case near the river. Others might have been built over, blocked off, or reclaimed by nature over the years. The opposite may be true, as well, when you suddenly come onto a road new enough to not yet show on most maps. It’s all part of the challenge — and the fun.

“I’m still trying to determine the difference between a street and an alley,” said Anderson. “Twice I rode alleys that the map said were streets.”

Above all, this should be fun. Savor the experience and the adventure and the exposure to new people and places that you don’t normally ride. If you find that the quest is becoming wearisome, there is no harm in taking a few days off or in riding another part of town.

“I had to take a break from Crestwood because so much of that city looks the same: ranch houses, concrete streets, and sweetgum trees,” said Anderson. “I kept thinking I was repeating streets, then I realized it all looks the same!”

Author: David Fiedler is a regular contributor to Terrain Magazine.

Leave A Comment