Dave Cummings is “a warrior” who always “pushes himself to his limit,” say friends from St. Louis’ cycling and skateboarding communities.

So, it made sense that during a 2019 vacation in Colorado, Cummings still wanted to skate after a two-and-a-half-hour bike ride up Berthoud Pass, a route in which you climb a half-mile of elevation.

He and his wife, Wendie, got coffee and then stopped at a skate park in Winter Park. Cummings did tricks for almost three hours.

“I was having a blast,” said Cummings, 51. “We were getting ready to leave.”

For his last trick of the day, the St. Louis native wanted to do a handrail slide. As he hopped on the metal rail, his board stuck, sending him flying forward.

When he landed, his left leg was fully extended.

“I felt and heard the bone break. I also was turning, so I dislocated my leg, and I felt that too,” he said. “I knew how bad it was.”

While he suffered a catastrophic injury because of his participation a dangerous sport, it was also fellow skateboarders and cyclists who have since helped lift him up financially and psychologically.

“It’s hard to be such an outdoors person, with an athletic background and then have to stop doing that completely for two years. The emotional support — it’s hard to put into words,” said Cummings.

Cummings knew how bad his injury was not only from the sound and feel but also because of his job. He studied occupational therapy at Saint Louis University and has worked in Mercy health system’s skilled nursing, orthopedics, trauma, and intensive care units.

“You really got to impact someone’s life after an injury or a big life-changing event, like a stroke or knee replacement, and help them get back to living,” he said.

When not working, Cummings excelled as an athlete. He started skateboarding at age 15, a decade before the first X Games, when the sport was still mostly an underground thing.

“He was one of the funnier guys in the crowd, but when it was time to take the discipline seriously, he was always trying to outdo the next person,” said Glen Stallings, who owned Altered Skates of America, which had shops in the St. Louis metro area between 1987 and 2004.

That drive led Cummings to win events throughout the country, including a vert ramp contest in the early ’90s in Cave Springs, Arkansas.

Dave Cummings at the Gateway Cup.

He also won bike races as a member of the Gateway Cycling Club. His first victory — and one of his most memorable — happened in 2001 at the Joe Martin Stage Race in Fayetteville, Arkansas. On the last of three races, a teammate, Doug Scronce, was in third place overall, which meant Cummings was working on his behalf. In the last lap, Cumming moved to the lead position of the team to allow Scronce to draft off him and then sprint to the finish.

“I was going so hard, I ended up winning the race,” Cummings recalled. (Scronce finished second in that stage and still won third overall.)

Mike Weiss, owner of Big Shark Bicycle Company, which sponsors the team, said Cummings “is really good at finishing.”

“There are a lot of decisions that you have to calculate to put yourself in a position to win, and Dave has been very, very consistent at that,” he said.

An Unfathomable Decision

When he fell off the skateboard, Cummings learned, his femur drove into his tibia and shattered the bone. On July 4, 2019, he had surgery in Denver. Over the next 16 months, he had eight more operations.

And still he was unable to move without crutches. As a team of doctors prepared to discuss his case, Cummings told his plastic surgeon: “An amputation is on the table.”

“I told him I really need to start moving forward, for me and for Wendie. Our whole life together, we traveled, and it was all about being active,” Cummings recalled.

A surgeon warned him that he would need an amputation above his knee, which as compared to one below it, made it especially difficult to walk. He could end up in a wheelchair at an early age.

But the other option was to have three more surgeries over the next 18 months — and then still possibly need the amputation.

Cummings decided to say goodbye to a part of the leg that had allowed him to surge forward on bikes and boards.

As he prepared to have the surgery last May in Columbia, Missouri, a pediatrician and fellow Gateway rider, Dr. Mark Murawski, dropped off a copy of the medical journal Missouri Magazine with an article about a new amputation procedure and prosthetic leg being developed at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Patients who have had “the Ewing Amputation have improved stability, improved motion path efficiency…and improved performance on torque control tasks” when compared to traditional amputees, the article said. “None of the patients experience muscle atrophy of the residual limb.”

Excited about the possibility, Cummings was able to reach the person leading the MIT trial: Hugh Herr, an engineer and double amputee who Time described as the “Leader of the Bionic Age,” because of his revolutionary work in creating robotic prosthetics that act like real limbs.

“I gave him my elevator pitch,” said Cummings, which meant explaining his surgical history, athletic career, and time as an occupational therapist.

The Road to Recovery

On July 7, Cummings underwent a successful amputation in Boston. Dr. Matthew Carty, the surgeon who performed the amputation, told him he had so much scar tissue in his knee that he had to break it to access the muscles. The doctor also told Cummings that more surgeries would not have enabled him to bend his knee and that he made the right decision to have the leg amputated.

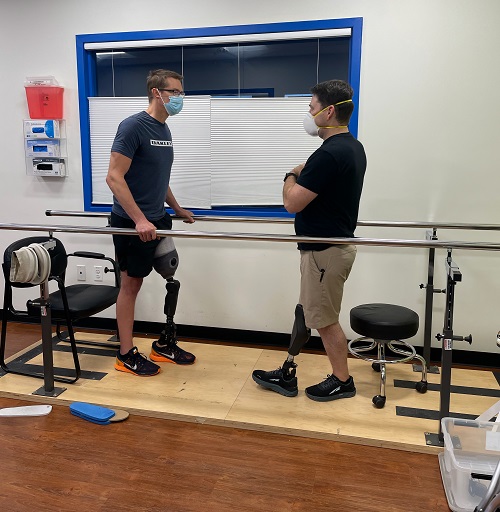

Dave Cummings (left) during physical therapy in Boston.

Cummings then entered familiar terrain — physical therapy — except this time other people were telling him what to do. In September, Cummings remained in Boston, wearing his new leg. He was able to walk without crutches and play ping-pong. His therapist told him he could hop on a real bike, but at press time Cummings hadn’t done so yet.

Meanwhile, back home, Stallings, Weiss, and other friends started a GoFundMe campaign to raise $100,000 for Cummings. Big Shark also set up a donation tent at the annual Gateway Cup criterium race, which Cummings competed in before his injury.

By September 29, they had raised nearly $46,000. The money will help Cummings purchase the expensive prosthetics. The insurance company would pay for one, but Cummings will need different legs for different activities. (The MIT trial prosthetic could still be five to 10 years away, Cummings said.)

He and Wendi have also spent significant money on health care. With no kids, they planned to retire in their mid-50s and spend their time on outdoor adventures. That will now have to wait.

In the meantime, Cummings said he is “motivated more than you can imagine” to walk, bike and hike — basically to “do as much as I can do.”

That doesn’t sound much different from his attitude before the injury.

As Weiss put it, for Cummings, the amputation was just a setback.

“And I just don’t think the setback is going to change much,” Weiss said. “He is still going to have an incredibly cool life, and he is still going to push himself.”

You can contribute to Dave Cummings’ GoFundMe campaign at gofundme.com/f/lets-help-dave-with-a-new-leg-and-a-new-life.

[…] who underwent an above-knee amputation following a traumatic skateboarding injury in 2019. (See the story from our November/December 2021 issue.) Since then, he has become an advocate for adaptive sports and spoke before the […]

[…] Everyone loves a good comeback story, and local athlete Dave Cummings has one. Terrain readers may recall that the competitive cyclist suffered a devastating skateboarding injury in 2019 that resulted in numerous surgeries, followed by the difficult decision to have his left leg amputated above the knee (see our November/December 2021 issue). […]