Setting foot in a rock climbing gym for the first time can feel otherworldly. The language sounds foreign. The footwear looks futuristic. The walls are prismatic. And the people seem to dangle from the rafters, laughing acrophobia in the face.

Nonetheless, you’re ready to give the vertical world a whirl — and we can’t blame you. It can be a life-changing experience.

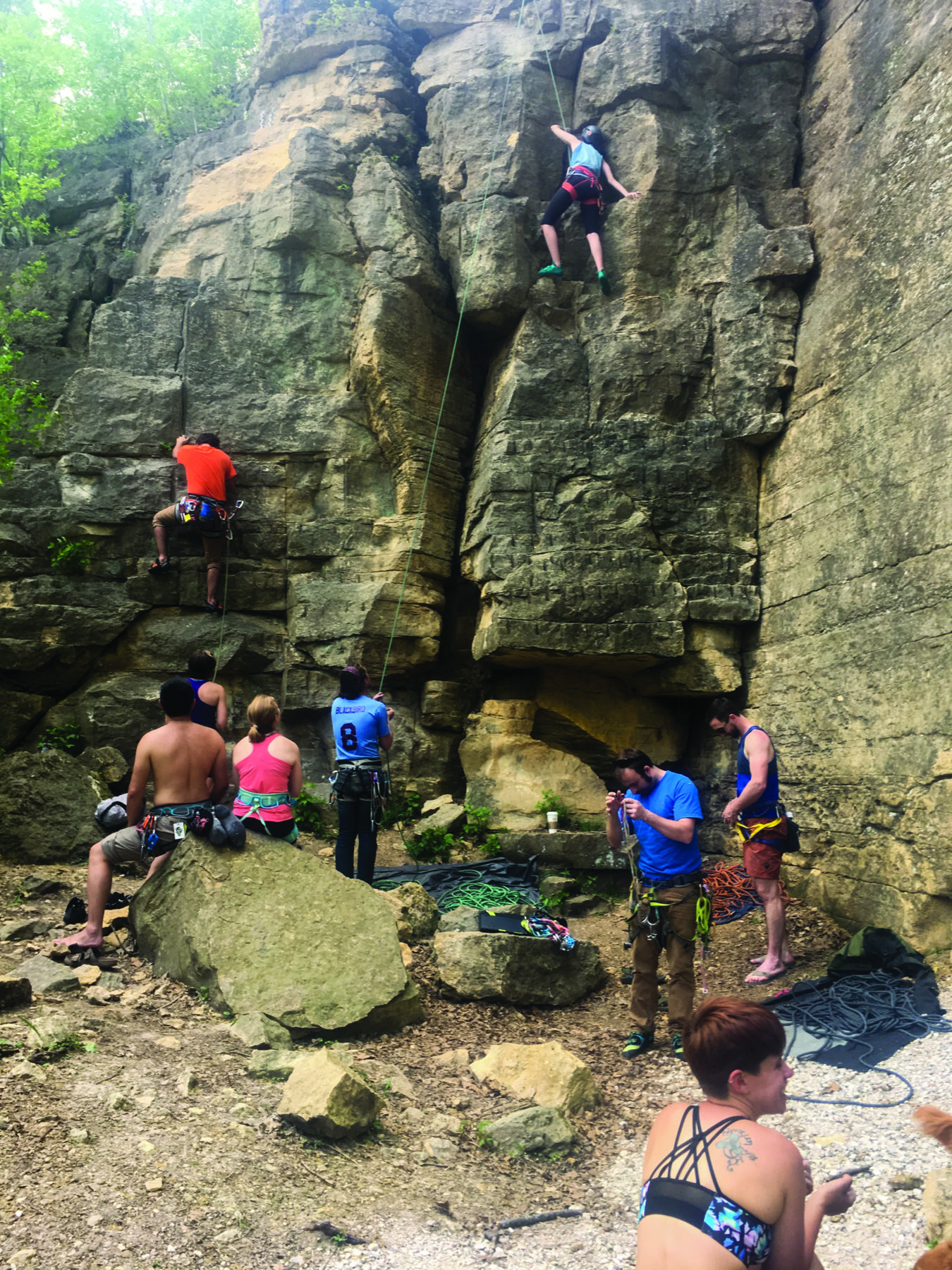

Climbing gyms and outdoor guides take much of the guesswork out of getting started. Gyms are designed for every skill level and offer rental gear. Guides tailor each outdoor adventure, taking people, equipment, and know-how straight to the crag.

As you consider your inaugural climbing session, it’s critical to get educated, starting with a chat about style.

Climbing Without a Rope. Bouldering is a form of rock climbing characterized by shorter walls that are climbed without the protection of a rope. Instead of a harness and rope, the boulderer’s gear is a duo of climbing shoes and chalk bag.

“I personally and currently prefer bouldering,” said Taylor Brown, a private instructor at Climb So iLL, a St. Louis-based rock climbing gym. “Bouldering is a fairly short set of moves on a shorter wall, called problems. People tend to think of it as a puzzle or a problem to solve.”

Seen the movie “Free Solo”? Famed climber, Alex Honnold, scales Yosemite’s 3,200-foot El Capitan sans rope. It’s known as free soloing (not the same as free climbing) and is among the sport’s most extreme disciplines.

Climbing With a Rope. Top rope, sport, and traditional (trad) climbing are all forms of free climbing (not the same as free soloing). Free climbing means climbers may protect themselves with gear, but they do not use any gear to pull up or step on as they would in aid climbing.

Most new climbers top rope climb because it poses the lowest risk, with pre-set ropes affixed to an anchor system above. A climber ties into to the sharp end of the rope with a belayer ensuring their safety from the other. Simply climb as high as you feel comfortable, knowing your max “fall” extends only as far as the rope will stretch. Alternatively, you can climb on your own using a gym’s mechanical, auto-belay systems.

In lead climbing, the climber must secure himself to the wall as he climbs a sport or trad route. In sport climbing, the climber starts with the rope on the ground and a harness full of quickdraws (two carabiners coupled by a semi-rigid material called a dogbone), then clips each draw into a bolt on the wall and feeds the rope through the other end of the draw. The same applies to trad climbing, except trad routes provide little to no fixed bolts or top anchors, requiring the climber to place protection (nuts and cams) into fissures in the rock.

“It’s generally a good idea to become comfortable belaying and climbing on top rope first,” said Brown. “Lead climbing is more advanced because there’s higher risk, longer falls, more endurance to clip the rope, and a more intense mental game.”

A Word on Grades

The Yosemite Decimal Rating System is the go-to rock climbing grading scale in the US. The easiest routes start at 5.0, with many of the pros climbing in the 5.16 range. These numbers are often followed by a +/- or a series of letters (A-D), which gives a more specific, albeit subjective, breakdown of what to expect.

The V Scale is bouldering’s open-ended grading scale, starting at V0 and currently topping out around V17.

Gearing Up

As you set out to procure the best bag o’ climbing gear, expect no shortage of options. What you climb ultimately determines what you need. For example, a harness and crash pad both keep climbers safe; however, a harness is as useless to bouldering as a crash pad is to roped climbing. Here are some pointers from local outfitters on getting your gear bag off the ground.

Climbing Shoes

If you stick with the sport, shoes will likely be one of your first big buys. “Purchasing a pair of climbing shoes is probably the best investment a climber can make,” said Jess White, operations and retail representative at Climb So iLL. “A beginner shoe is shaped more like a sneaker [neutral] than an upside-down letter U [aggressive] and fits snuggly and somewhat comfortably.”

Harness

All climbing gear, including harnesses, are engineered for safety and attuned to specific applications. Gym and sport climbing harnesses are lightweight, not requiring extra loops for a trad rack or lumbar support for big wall climbing. Try them on and pay attention to fit and comfort.

Belay Device

To keep a climber safely airborne, a belayer feeds a rope through a belay device, which operates by bending the rope and creating friction. The two most common types are tube-style (ATC) and brake assisted. “An assisted braking device has a failsafe system, which cinches the rope automatically,” said Faith Whatley-Blaine, a coach at Upper Limits Indoor Rock Climbing Gym. “An ATC does not have a backup system.” Brake-assisted devices like the Petzl Grigri or Edelrid Jul are costlier and take some practice, but their load-locking ability makes them conceptually safer.

Rope

Trading the security of a top rope for the thrill of connecting one fixed protection point to the next when lead climbing takes commitment and the right rope for the journey. First and foremost, the rope must be dynamic, meaning it will stretch and absorb the impact of a fall. A standard, single rope is 60- or 70-meters in the mid-to-upper 9mm range.

Crash Pad

Bouldering in a gym requires nothing more than shoes and skill. Mother nature, however, is not equipped with built-in cushioning, making this mattress-like apparatus a must for outdoor boulderers. In addition to a variety of brands, styles, and sizes, White suggests, “focus(ing) on the thickness, density, closure system, and carrying options.”

Essential Skills

Good climbers don’t muscle up 50 feet of vertical terrain. Good climbers rely on technique. Long before perfecting the bat hang or sticking a high-flying dyno maneuver, amateurs learn to move with precision, maintain balance, and meticulously conserve energy. Upper Limits’ Whatley-Blaine offers three foundational skills.

Use Your Legs

Rock climbing is more akin to ascending a ladder than doing pull-ups. “When I first started climbing, I had very little upper body strength. Meanwhile, I walk all day. Naturally, my lower body is stronger,” said Whatley-Blaine. “Rely on the muscles you already have by using your lower body to push you up the wall and your upper body to balance.”

Use Your Arms

Good technique improves efficiencies, keeping muscles rested and ready for the task at hand. Bent arms engage muscles and exert energy, while straight arms shift the load to your skeleton. “It’s a game changer,” said Whatley-Blaine. Nonetheless, forearms do fatigue, so at each jug (big hold), shake out the pump (muscle contractions).

Use Your Body

“Keep your hips, your center of gravity, and your core close to the wall,” Whatley-Blaine explained. “If I make a move with my right hand, I put the outer edge of my right shoe on the foot hold. Whatever hand I’m reaching up with, that’s the hip that should be closest to the wall.” With practice, turning a hip to the wall can maintain balance and extend reach.

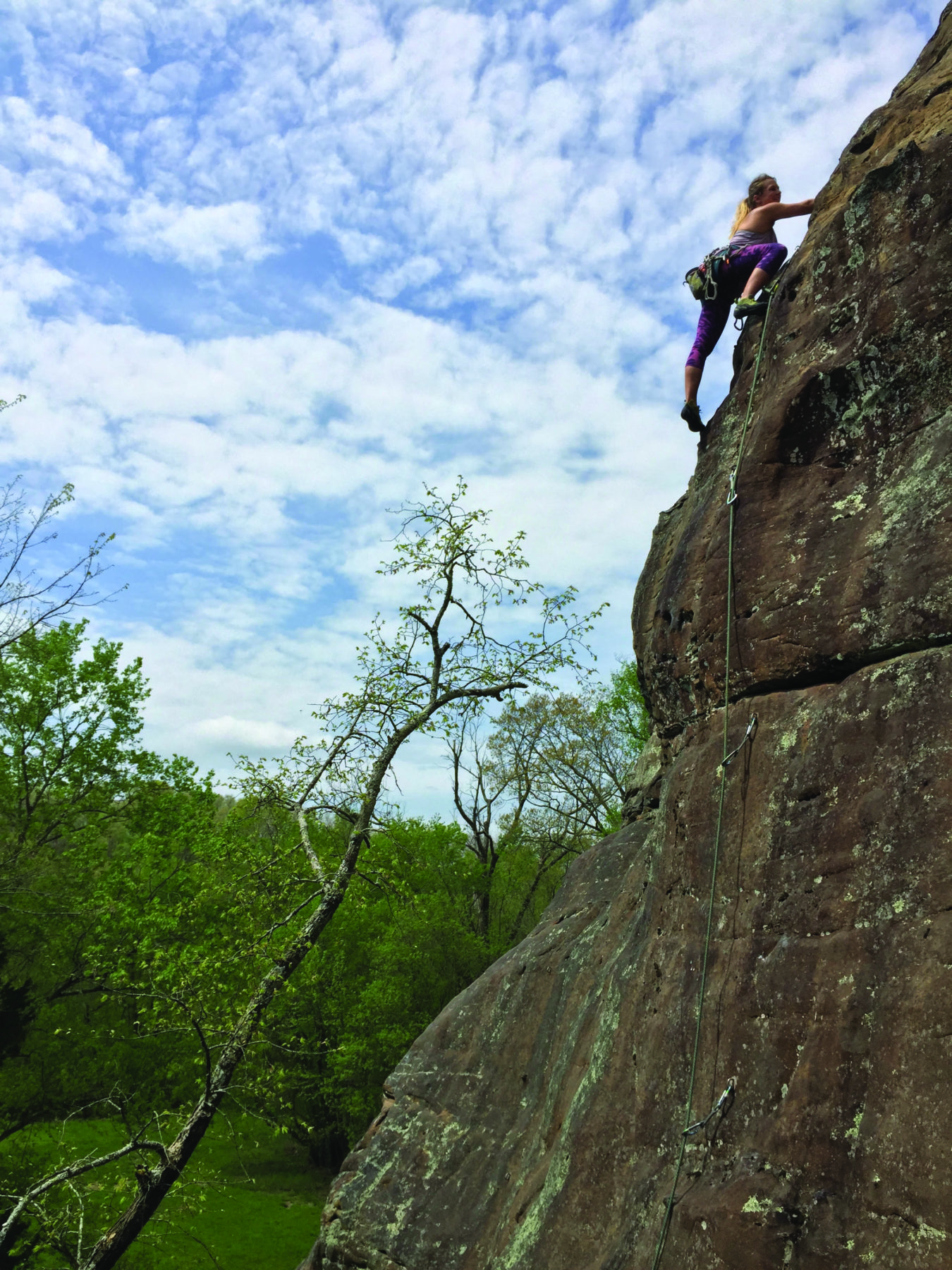

Gym to Crag

Indoor and outdoor rock climbing are not parallel play. The same sport, absolutely. Identical, not a chance. The list of differences is long: color-coded plastic versus earth-tone rock, music blaring versus sounds of nature, padded floors versus solid ground, climate controlled versus controlled by climate.

Most climbers are drawn to the real deal; however, taking the leap to climbing outdoors can be even more intimidating than showing up to the gym for the first time. The skills needed are greater, the variables are many, and the stakes are absolute.

Jon Richard, owner of the St. Louis-based tree and rock climbing guide service Vertical Voyages, says that one of the biggest differences is the unknowns. Indoors, the sequence of the new jug haul may be the day’s only mystery. Otherwise, grades are fairly consistent. Each protection point is equal to the former. Routes conclude with top anchor hooks. Bathrooms are around the corner. And help is always nearby.

These rarely apply to the wonderful world of outdoor climbing.

A helmet is a no-brainer when climbing outdoors. (Vertical Voyages)

Richard offers a list of considerations to help climbers identify unknowns, mitigate risks, choose the right gear, and mentally prepare for a climb: How tall is the route? Are the anchors mussy hooks, chains, rap rings? Is it a mixed route? How does it protect? Are there fall risks? When was it put up? Can I recognize a sketchy bolt? Did I close the system?

Systems

According to Richard, who is an American Mountain Guide Association (AMGA) Certified Rock Guide and Single Pitch Instructor, the four basic elements of a safe climbing system are: anchors, climber, belayer, and rope. When taking the four-part system outdoors, be mindful of the differences in application.

Anchors. Outdoor sport routes only supply bolts and anchor rings, while the sport’s indoor adaptation is fully equipped with fixed quickdraws (permadraws) and top anchor hooks. Going from gym to crag not only requires additional gear — quickdraws, slings, locking, and non-locking carabiners — but also the ability to properly place and safely retrieve gear.

Climber. Because gym climbers can get locked into following color-coded paths, the combination of an outdoor crag’s colorless wayfinding and extra gear placement can dial them back several grades. Gym-learned knowledge, like how to avoid back-clipping and Z-clipping, must be augmented with vital new information pertaining to direction of travel, loading the spine, setting anchors, and inspecting bolts. Outdoors, a helmet is a no-brainer and a stick clip can save your ankles by allowing you to clip a roped-up quickdraw to the first bolt from the ground.

Belayer. Because protection points on outdoor routes are further apart and not equidistant, a belayer needs to know where to stand and how to compensate. Notice that shelf at the third bolt? Adjust the slack so the climber doesn’t break an ankle. For your climber’s sake, wear a helmet and use a brake-assisted belay device. Rocks fall, bees sting, and any number of hazards could distract or even incapacitate the most experienced belayer.

Rope. Preemptively avoid falling off the end of your rope by ensuring it’s long enough. Yes, it happens. “Don’t assume your rope is long enough,” Richard cautioned. “Tie a knot in the end of your rope and close the system all the time, always.” Once safely on the ground, unknot it before pulling the rope…or you’ll be sorry.

Increase Safety

Climbing is a high-stakes sport in which errors can turn catastrophic. Increasing safety starts with identifying and managing risk. For example, I’m aware that rocks can fall (identifying risk), therefore I wear a helmet and avoid areas under the climber (managing risk), making myself less likely to get clocked (increased safety).

“Develop a sense of awareness,” Richard said. “Devote 100 percent of your attention to the current task — belaying, tying in, cleaning a route. Don’t get distracted, and don’t be distracting.”

Get Good Knowledge

The transition from indoor climbing to its incredible outdoor correlative starts and ends with education. It takes more than can be absorbed by article, book, or video. There’s truly no substitute for experience. Hire a certified guide. Take a gym-to-crag class. Or check out a festival like the American Alpine Club’s Craggin’ Classic to learn new skills alongside other climbers.

“A lot of climbers learn from friends, and that means we’re only learning what our friends know,” said climber Erin Leigh Coates. “If you have talented, accomplished friends who value safety and value doing things the right way, then that’s great. But if you have friends whose risk assessment and evaluation doesn’t align with yours, it’s hard to know what you’re learning.”

Where to Go

Getting the lay of the vertical land is as easy as checking out your gym’s selection of local guidebooks and perusing the Mountain Project website (mountainproject.com). To get you started, we’ve picked three local crags known for their quantity and quality of moderate routes.

Giant City (Southern Illinois)

Giant City’s grip-friendly sandstone is rich with iron and presents a broad range of features and grades with a quick, 60-second approach. Giant City climbing is pumpy and powerful, with a smorgasbord of chimneys, gullies, roofs, traverses, aretes, slabs, and caves. With 35 routes under 5.9, it’s a great place to start outdoors.

Pere Marquette (Grafton, Illinois)

The largest state park in the Land of Lincoln sports more than 70 routes. Characterized by relatively short limestone bluffs, Pere Marquette caters to beginner-to-intermediate climbers who don’t mind a panoramic view of the Illinois-Mississippi Confluence. Sport climbing makes up 60 percent of the climbing, with more than 30 routes under 5.9.

Robinson Bluff (Tiff, Missouri)

This privately developed climbing area, located 60 miles south of St. Louis, has some of the tallest and most concentrated climbing in Missouri. Its 3,600-foot bluff line follows the Big River and overlooks picturesque farmland. Several of its 200+ bolted routes exceed 100 feet, and more than 55 routes have grades under 5.9.

Behave Yourself

Rock climbers have long been known for their rebellious and nonconformist subculture. Yet even we abide by a (somewhat) universally accepted set of ethics and etiquette. That’s because our every choice to be or not to be courteous of people and places has shared repercussions. As limited outdoor destinations increasingly overflow with other lovers of the sport, it’s never been more important to have good climbing manners.

Pack In, Pack Out

This is the basic rule of being a good steward. Conservation, safety, and continued access rely on all outdoor user groups limiting activities that crush vegetation, create erosion, affect wildlife behaviors, or pollute the outdoors with food debris, trash, and, yes, poop.

Don’t Sprawl

Large spreads of gear and equipment, crag dogs, and caravans of climbers could each have a category of its own, but the gist of going “sprawless” is keeping belongings, pets, and groups both minimal and managed. It means don’t block trails, keep pets leashed, and leave the crowds for the gym.

Shhhhhh!

The artificially noisy atmosphere that epitomizes indoor rock climbing can be an outdoor climber’s nightmare. Nothing stifles a one-with-nature experience or muddles the two-way communication between climber and belayer like 110 decibels. More than inconvenient, it’s dangerous. Oh, and no one wants unsolicited beta!

Ultimately, good climbing etiquette comes down to being a good steward and not being a jerk.

Author: Corrie Hendrix Gambill is a regular controbutor to Terrain Magazine.

Top Image: Climbing at Holy Boulders by Antonio Jacob Martinez.

Leave A Comment