On a chilly Friday afternoon last November, more than 150 people from across the country assembled in a large convention hall in St. Charles, Missouri, for the 2024 Gateway Outdoor Summit. During the four-hour event, which was presented by River City Outdoors (the parent organization of Terrain), attendees and featured guests held many thought-provoking discussions about the future of outdoor recreation in the region.

For example, Emma Klues from Great Rivers Greenway provided an update on the Brickline Greenway, a network of accessible paths that aims to connect St. Louisans to their parks, neighborhoods, and cultural institutions. (Estimated completion: 2030.)

Rick Mihalevich from Friends of Rock Island Trail State Park gave a progress report on the Rock Island Trail, a 200-mile rail trail that, if completed, would connect to the Katy Trail and form a sprawling 450-mile bike loop across Missouri. (Estimated remaining cost: $100 million.)

And Lesford Duncan, executive director of Outdoor Foundation (the philanthropic arm of Outdoor Industry Association), capped off the Summit with a multimedia keynote presentation that emphasized the importance of breaking down barriers and fostering a love for nature across diverse communities.

But perhaps the most intriguing conversation of the afternoon occurred in a panel titled “Big Ideas for Outdoor Recreation in the Great Middle West.” In this session, Chris Perkins, vice president of programs at the coalition Outdoor Recreation Roundtable, made the case for establishing a state office of outdoor recreation in both Missouri and Illinois.

Perkins’ pitch, in a nutshell, went like this: Outdoor recreation is big business. In 2023, according to federal data, Missouri’s outdoor recreation economy — everything from hiking and cycling to boating and fishing — generated $9.9 billion. That’s over $3 billion more than Missouri’s agriculture industry. Yet, unlike agriculture, outdoor recreation holds no office in Missouri’s state government. (Illinois has no office of outdoor rec either.) That’s a problem, argues Perkins.

“Outdoor recreation deserves a seat at the political table,” says Perkins, “just like any other core sector of the U.S. economy.”

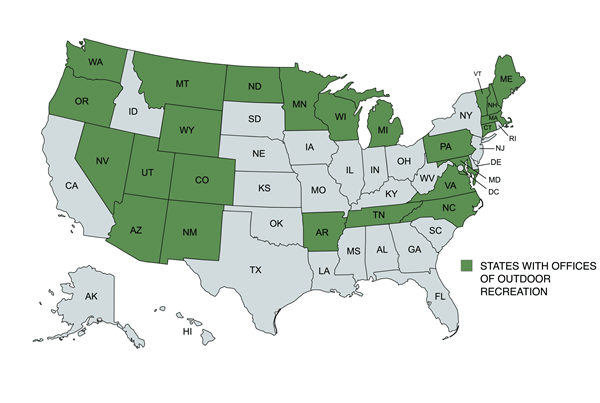

Currently, 24 states have offices of outdoor recreation. (Outdoor Recreation Roundtable)

A National Trend

In 2013, Utah became the first state to create an office of outdoor recreation. Since then, 23 other states have followed suit. These include places with both Democratic governors, like Michigan and Pennsylvania, and Republican governors, like Arkansas and Tennessee.

Why is nearly half the country rushing to open these state offices? Such offices create a centralized home to coordinate outdoor recreation efforts across agencies, says Perkins, and they identify new opportunities for economic growth. In short: These offices help big projects get done. (Along those lines: Remember the Rock Island Trail project mentioned earlier in this article? Perhaps an office of outdoor recreation could help find the necessary funds to make it a reality…before the year 2050.)

Of course, convincing a state government to establish a new office is no easy task. Perkins recommends a five-step plan. These steps include building a bipartisan coalition (i.e., businesses and leaders who are passionate about the outdoors), finding allies (i.e., state legislators and donors), creating a mission, choosing a path, and asking for help.

Others at the Summit seemed to agree with Perkins’ plan. One such person was Greg Brumitt, a Metro East resident and founder of the community development group Active Strategies.

“We have to be grown up about how we approach politics and money,” Brumitt says. “We are a big industry. We need to better understand this. We need to define what we’re doing and figure out how we can come together.”

Author: Shawn Donnelly is the managing editor of Terrain.

Top image: Chris Perkins of Outdoor Recreation Roundtable (second from left) at the 2024 Gateway Outdoor Summit. (Alex Noguera)

Leave A Comment